If you find yourself wandering into an Italian restaurant in New Orleans on March 19, you may be surprised to find it unusually crowded, with people standing around chatting loudly, exchanging recipes, drinking, and enjoying an assortment – no doubt a plateful – of fresh Italian treats. But beyond the crowds of people, you may find a large, three-layered altar dedicated to St. Joseph, heavily adorned by Catholic iconography, elaborate pastries, dozens of fava beans, cakes, candles, plants, and many more. The feast day of St. Joseph is one of the most important days for Italian Americans, and the St. Joseph’s Altar has become the hallmark symbol of this celebration. The St. Joseph’s Altar takes weeks of preparation and is typically a means of bringing the Italian community together to celebrate their heritage and, of course, eat. Traditionally the altar has three levels, representing the Trinity, adorned with statues of each member of the Holy Family. Food covers the altar in gratitude to St. Joseph for alleviating hunger, representing abundance. It is traditional for the remaining edible portions of the altar to be donated to give back to the community. This celebration is said to have originated in New Orleans as a result of Italian immigration in the early 1800s. The altar stood as a testament to all the traditions and practices passed down from generations before, but soon the altar itself became a tradition to pass on and celebrate. For my family, the altar has remained an important reminder of where we come from, and it has been the responsibility of each generation to continue the practices and stories of their predecessors. No matter how young I was, my grandparents always found it important that I be a part of the preparation and celebration.

One of the essential components of the altar are the various fig creations which decorate it. Figs could appear in a variety of different confections, from cakes, to bread, to large ornamental work-of-art pastries resembling famous Catholic symbols. Most common among them are the cuccidati, what people often call “Italian fig cookies,” the bite-sized treats with a fig filling that are typically decorated with frosting and sprinkles. The recipe that my family uses for our fig cookies has been passed down for generations, but in 1996 my grandmother decided to write the recipe down for the very first time. From there, the recipe has been passed down, to my mother, and now to me. But the generational tradition of passing down this and other recipes is not solely about the food. Learning to cook and bake with my family has always meant learning a history lesson. Almost as important as the recipe itself are the stories that interconnect with each and every different creation. When growing up and learning to make the cuccidati with my grandmother, she would tell me stories of her own mother and grandmother. Now, my mother and I discuss my grandmother in the same way in the kitchen, often reciting some of the stories she would tell us or telling our own stories and memories of her. The kitchen has become a hub of family history in our family, with everything from recipes to utensils being family heirlooms. The fig cookies serve as a small but tangible reminder of my own role in the preservation of my family’s history.

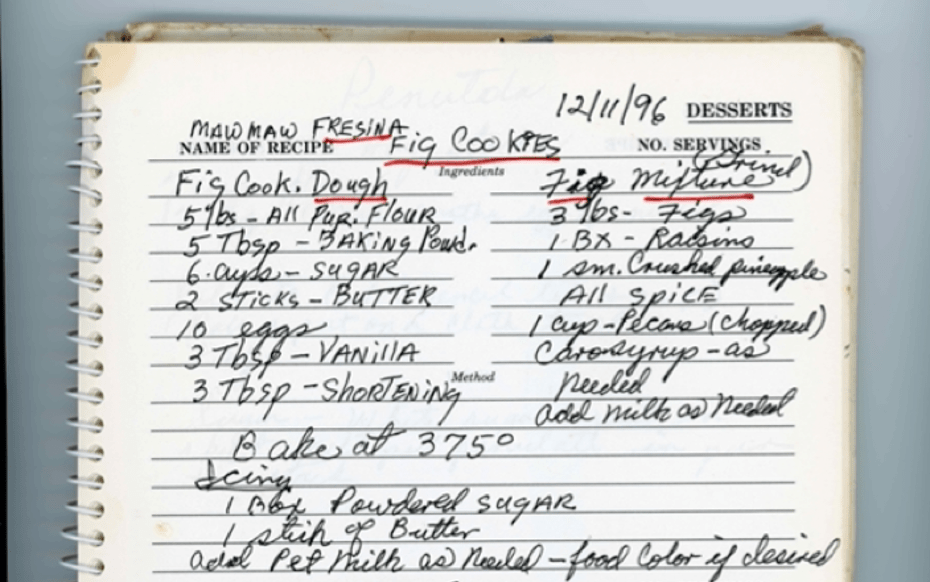

Maw Maw Fresina’s Fig Cookies

Fig Cookie Dough

- 5 pounds of all purpose flour

- 5 tablespoons of baking powder

- 6 cups of sugar

- 2 sticks of butter

- 10 eggs

- 3 tablespoons of vanilla

- 3 tablespoons of shortening

Fig Mixture

- 3 pounds of figs

- 1 box of raisins

- 1 small crushed pineapple

- Allspice

- 1 cup of chopped pecans

- Cane syrup as needed

- Add milk as needed

Bake at 375 degrees

Icing

- 1 box of powdered sugar

- 1 stick of butter

- Add pet milk if needed – food coloring if desired

It is not particularly surprising that a recipe passed down through generations would come with few actual instructions. Recipes such as these are primarily meant to be an ingredients inventory, whereas the methods involved in making these fig cookies would have passed down orally. Every Italian family has their own iteration of how this cookie is made, typically pertaining to what was available to the immigrant families in the late 1800s and early 1900s. It was in this time period where canned fruits and vegetables started becoming readily available and affordable. In this recipe, crushed pineapple is used, but it is also very common to see lemons or oranges used instead. Other recipes call for almonds or walnuts rather than pecans, but pecans were much more common in the United States than almonds or walnuts, which are more European and Mediterranean options.

The use of figs in many different creations on the altar, and specifically in the cuccidati, are of course deeply rooted in Italian history and culture. Firstly, they are a clear allusion to the abundance of fig trees throughout mainland Italy and, perhaps most especially, Sicily. Conveniently for Italian American immigrants who settled in areas such as New Orleans or Hammond, fig trees are also plentiful in Louisiana. But even more than just a nod to the inflorescence of the homeland, figs have a deeper connection to religion. In Catholicism, the fig tree is seen as a reminder of the Kingdom of God, and by adorning the altar with fig creations, these creations themselves may serve as a reminder of God’s closeness with the participants.

The process of making the cookies is really quite simple. The most difficult part comes with getting the fig filling to just the right consistency. You want the filling to be a paste consistency, but still slightly chunky, while simultaneously adding in the pecans. The pecans and the fig seeds give the cookie an incredible crunch mixed with the sweet flavor of the fig and the icing. The other challenge may be decorating. When it comes to the St. Joseph’s Altar, every piece comes highly decorated with intricate designs cut out of the dough, beaded ornamentation, or complicated icing work.

All four of my maternal great-great-grandparents immigrated to the United States from Sicily throughout the 19th century. I often think about what it must have been like for them to leave behind their homes, and in some cases their families, to come to a land they knew very little about. As my grandfather likes to remind me, they could not even speak English when coming over, so it is no wonder that Italian immigrant communities, like those in New Orleans, found it so important to carry on their traditions with their communities. My family settled in the small town of Independence, Louisiana, which has since become famous for the Independence Sicilian Heritage Festival and Festival of St. Joseph, two celebrations of Italian ancestry that are extremely important for the community of Italians that live there. Long before I was born, the St. Joseph’s Altar has been an annual tradition in my family during the festival of St. Joseph in Independence and every year members of my family and the community gather together and begin preparing weeks ahead for the celebration. Some of my earliest memories are of creating my very own pieces for the altar, from pupacalovas, a small basket made of dough around a dyed egg in the center to represent Easter, large cuccidati in the shape of the sacred heart or the monstrance, the St. Lucy Eye Pie, a sort of fig pie that is designed to resemble the platter with which Saint Lucy carries her eyes, and of course the classic fig cookies.

It is now much more common for a St. Joseph’s Altar to be held in a church community center, but back in the 19th and 20th century, it was far more common for the altar to be hosted in the home of a member of the community. For my family, we have a documented history if hosting the altar in our homes. In 1971, my great grandparents hosted the altar in their own homes, with members of the community coming together to cook, prepare the fig creations, and decorate the altar. In 2011, my family hosted the altar at our home. Being fairly young, I remember this being the first time I truly understood what the celebration meant to my community and to my heritage. The altar had hundreds of visitors and I had an active role in the construction and preparation of the altar. I learned a great deal about my family history that year throughout the process by cooking and baking with my family members. It was the very first time I felt as though I was pivotal in the tradition, and that the role had been passed to me. The first thing that I was tasked with learning to make that year was the cuccidati.

The St. Joseph’s Altar has always been a symbol of my family’s genealogy, providing us with important lessons about our ancestors, their beliefs, practices, and their methods of food preparation. The celebration of the altar has not only been a great medium to become involved in my community, but also a tangible way to remember and learn from my ancestors. Like with celebrations such as Dia De Los Muertos, we use the altar as an opportunity to reflect on the dead and what they have passed on to us. To some, that may look like a list of ingredients scribbled down on a paper, but for my family and I, it represents much more. My grandmother, from whom I learned most of what I know about the altar, has now passed away. But she has left behind a recipe, not only for food, but for faith and family, that I may use to make my very own fig cookies. In this way, the responsibility has been passed on to me to carry on the traditions of my ancestors, and I look forward to sharing the tradition of the fig cookies and all they have come to symbolize with my future family.