The food culture of Puerto Rico reflects its tumultuous relationship with the United States, revealing the convoluted interplay between the two divergent cultures. A famous restaurant located in San Juan, Puerto Rico, called La Mallorquina is a prime example of the mixture of these cultures during an intricate moment in time between the United States and Puerto Rico. In order to understand why this menu holds such significance as a lens into Puerto Rico’s political, social, and cultural context in the 1950s specifically, we must first examine the individual historical context between the United States and Puerto Rico itself before and during the 1950s.

La Mallorquina itself is known as one of the oldest restaurants in the Western Hemisphere dating back to 1848.1 This restaurant served the first self-elected governor of Puerto Rico, Luis Muñoz Marín, whose relevance and importance will be discussed later on, but this in itself is enough to highlight its deep rooted ties to Puerto Rican culture.2 In the 1930s, the United States, specifically the U.S. appointed Governor Winship, attempted to advertise Puerto Rico as a destination hot spot.3 The United States often advertised Puerto Rico as a fantasy land where you had beautiful beaches, golf courses, and deep sea fishing, while all the while belittling the people of Puerto Rico by making them out to be dependent, uncivilized, and as “others” compared to Americans. Although, not “other” enough to not be patriotic- in many cases Puerto Rico was advertised to be perfect for its exoticism and familiarity, since there was a different language, culture, and people but there was still English and American currency.4 In some advertisements, you can very clearly tell that the ad itself was based on common American advertisements that were geared towards men by showcasing the beautiful women of Puerto Rico just waiting for these nice business men to show up and spend their vacation with them. While this showcases one side of the Puerto Rican sales pitch, there was simultaneously an image being portrayed of Puerto Rico that it was a place of need with people in need, that was dying for American intervention, tourism, money, and the presence of Americans themselves.5 What better way to make yourself feel good than to vacation on a beautiful beach and be a hero while doing it. At the same time Americans were idealizing Puerto Rico, Puerto Ricans were waging their battles both for and against Americans, American leadership, and American culture.

Much of the unrest in Puerto Rico was directed towards the United States’ appointed officials of Puerto Rico. Governor Blanton Winship was appointed to instill military control and fear towards rising nationalist groups that advocated for overthrowing United States leadership.6 Some highlights from Winship’s time in office include playing an active part in maintaining Puerto Rico’s poverty, fighting for the exclusion of minimum wage laws for Puerto Rico, and two massacres- all leading to his removal from office.7 These events, alongside overall pressures from hurricanes and economic Depression, created the perfect atmosphere for Nationalist Party president, Pedro Albizu Campos, to strongly influence political attitudes- specifically against U.S. rule.8 Puerto Rican citizens also began voicing their dissent towards Americans and American culture which pushed for reformation on a political, social, and cultural level.

In 1949, the United States allowed Puerto Rico to self-elect their governor for the very first time.9 Puerto Rico overwhelmingly chose Luis Muñoz Marín, a senator who had previously organized the Popular Democratic Party of Puerto Rico that combined moderate commonwealth foundations with populist economic ideologies.10 This party took on a mascot, a straw-hatted farmer, that symbolized Puerto Rico’s pride in their rural culture that had been diminished with American colonialism.11 The Popular Democratic Party’s slogan was “Pan, Tierra, y Libertad” (Bread, Land, and Freedom), which symbolized land redistribution, new jobs, and economic promises that were led by farmers, unemployed workers, and the middle class alike.12After being elected, Luis Muñoz Marín immediately began his fight for commonwealth status in Puerto Rico- a compromise for Puerto Rico to be more independent while still maintaining good relationships with the United States by conceding to overall foreign affairs still being under U.S. control13. His previous senatorial efforts and works had gotten him his election into office, but Muñoz Marín soon had to come to terms with American colonialism’s impact and necessary involvement to grow Puerto Rico’s economy, making compromise a repeating theme in all his legislative and social campaigns that would undoubtedly influence a cultural and social shift to do the same.

Luis Muñoz Marín then established locally created, regulated, and run tourism and promoted exports to improve Puerto Rican economy since it almost solely depended on the involvement of American consumerism.14This is often referred to as Puerto Rico’s “Operation Bootstrap”15 where Puerto Ricans aligned themselves with the American mindset of improved economic conditions through hard work rather than help. Although seemingly contradictory, the creators and followers of Operation Bootstrap were under an understanding that the social equality many of the rural population was fighting for would only be possible through foreign economic intervention.16 Since air travel boomed in the 1950s17, Luis Muñoz Marín took advantage of this opportunity and focused primarily on his efforts to improve Puerto Rican conditions and economy by taking into consideration and applying American colonialism in a way that most benefited Puerto Rico. Luis Muñoz Marín did take note of the overwhelming dissent towards American tourism and publicly took a stance against the already existing portrayals of Puerto Rico being sold to America.18 In order to keep social capital and improve Puerto Rico’s economy, Luis Muñoz Marín had to reinvent Puerto Rico as an island dedicated to modernity and self-reliance. The campaign for tourism required serious effort to reimagine the charms of Puerto Rico that repudiated ugly stereotypes promoted by the Winship era and appealed to Americans and Puerto Ricans alike.

Having almost completely renovated and reinvented more than just tourism and the economy, Puerto Rico managed to create major attractions and infrastructure that were Puerto Rican owned, created, and funded.19 Luis Muñoz Marín then appointed the head of Formento’s Tourism Bureau, J. Stanton Robbins, who began publishing magazine articles in English to update Americans on major attractions in Puerto Rico Qué Pasa in Puerto Rico.20 Publications including the New York Times, Travel, and Saturday Review all began to publish snippets, articles, and advertisements that included all the culture, architecture, history, and beauty of Puerto Rico. Eventually, Puerto Rico even established a Tourism Bureau office in Rockefeller Plaza in New York21 and went on to provide training classes for basic English speaking skills to Puerto Rican citizens that would come into contact with possible American tourist.22 Puerto Rico’s newfound success in tourism undoubtedly relieved economic troubles, but not without criticism by key local figures. Many claimed that Puerto Rico sold itself to American tourism, but Luis Muñoz Marín defended his decision by noting that tourism funded educational and social welfare.23 Many Popular Democratic Party leaders mirrored his sentiments in that most of Puerto Rico was still recovering from the economic Depression, and to be able to fix Puerto Rico’s most pressing matters like work labor, unemployment rates, and a rapidly growing population, they had to industrialize. Although anti-tourism sentiment grew alongside the tourism industry, both Marin and tourism remained popular and essential parts of Puerto Rican culture and economy.

In the 1950s, Americans and Puerto Ricans alike agreed in embracing modernity while keeping traditional and conservative cultural roots in place, and Puerto Rico learned to perfect the art of balance by putting the digestible and even appreciated parts of their culture up at the forefront of the American experience while still adapting enough to keep American comfortability intact. San Juan soon became the Puerto Rican government’s testing ground for luxury tourism since it was antique and fast growing population.24 The people in San Juan’s median income was double that of the rest of the island, making it a lot nicer than other cities, yet the Puerto Rican government advertised it as authentic since Luis Muñoz Marín still understood that Americans wanted luxury.25 Most of Puerto Rico’s major attractions in the 1950s were all a response to the previous history between Puerto Rico and the United States and a desire to balance Puerto Rican tradition and American modernity.

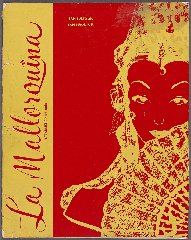

La Mallorquina attempted to recreate this same harmony between authenticity and American ease. Founded in San Juan in 1848,26 the restaurant has long identified with Puerto Rican food and culture. The owners were originally from Mallorca, Spain,27 and in the menu you can see not only traditional Puerto Rican foods but traditional Spanish foods like turrón, asopao, and paella a la Valenciana . Being as old as it is, at any point in time, La Mallorquina could have chosen to adapt the menu to accommodate the Puerto Rican palate, but they did not. In the selected menu example, though, you can clearly also see foods that would have been welcomed by the typical American palate like bacon and tenderloin steak. The menu itself is also fully translated into English. The translations and wording of the menu itself are also very telling. Rather than just listing “fruit salad”, it is explicitly stated that the fruit is “Caribbean” in English while saying “from [Puerto Rico]” in Spanish. This is a clear indication of La Mallorquina responding to the desires of both Puerto Ricans and Americans and advertising accordingly. Puerto Ricans would have wanted to know that the fruit they are eating are sourced locally which would not only mirror previous political sentiments to support local businesses and farmers, but it would also mean the owners were making an active effort to put their money back into the Puerto Rican economy. On the other hand, by labelling it specifically as “Caribbean” fruit salad, they were directly playing into the selling of Puerto Rico as “Caribbean tourism”- as most of Puerto Rico would have been advertised in the 1950s.28

Even when you look at the very front of the menu, although simple, it tells a lot about the time period in which it was made. Within its simplicity, it is embracing the modernity of American menus at the time. In its color, though, it stays true to its Spaniard roots by embracing the bright red and the gold color pattern that is found in the Spaniard flag. On its cover there is only the date and place in which it was established. Its blatant antiquity and high-end location in San Juan, Puerto Rico showcased the traditionalism and luxury that Puerto Ricans and Americans would have desired. La Mallorquina was also fighting against other restaurants at the time that were opening and advertising a diverse cultural experience from the comfort of Puerto Rico.29 Puerto Rico began to see Chinese, Swiss, and a variety of different cultural restaurants open as tourism continued to expand.30 These restaurants were almost always located in or around high-end restaurants.31 La Mallorquina keeping its Spaniard roots present and clear while also advertising a fairly racially ambiguous woman at the forefront wearing traditional Asian clothing was their grasp at fulfilling all American desires to eat authentic, exotic, and luxurious.

When one visits La Mallorquina today, it is clear that many of the ideals it adopted in the 1950s remain. Although having closed and recently opened back up, La Mallorquina has kept its “local” feel by keeping its open window restaurant experience, as can be seen by one reviewer’s self-uploaded photos from “Tasting PR”. This type of dining would have been very popular in the 1950s and throughout so people could enjoy the fresh air and Puerto Rican climate while enjoying their vacation lunch or dinner. Alongside this, La Mallorquina is included in the popular “Discover Puerto Rico” website , which self describes La Mallorquina as a cultural melting pot through its foods and history, further proving its desire as a restaurant to really sell the idea of authenticity and diversity. Under the description of the menu, there is an ad for days-long tours around Old San Juan to view their historical architecture, learn about their history, and experience the bigger attractions- very much just a modern day version of the travel packages and New York Times advertisements for San Juan found in the 1950s.

Overall, La Mallorquina and San Juan have historically kept true to their ideals of keeping up with modernity and contemporary cultural waves, while still passionately maintaining Puerto Rico’s rich cultural heritage, beautiful architecture, and pride. La Mallorquina’s 1958 menu is only one example of this complex and convoluted history to get to a place of balance and compromise as a culture and people who are proud of their history and culture, while still being an island that is technically under the supervision of a fundamentally different cultural, economic, and political entity. Much like Luis Muñoz Marín pushed for compromise to further growth and peace, restaurants like La Mallorquina did the same to make the best of their situation by appealing to both the people of Puerto Rico as well as potential Americans that proved essential to the Puerto Rican economy

Footnotes

- “La Mallorquina”, Discover Puerto Rico, accessed December 10, 2021, https://www.discoverpuertorico.com/profile/la-mallorquina/3792.

- “La Mallorquina”, Discover Puerto Rico, accessed December 10, 2021, https://www.discoverpuertorico.com/profile/la-mallorquina/3792.

- Dennis Merrill. “Negotiating Cold War Paradise: U.S. Tourism, Economic Planning, and Cultural Modernity in Twentieth-Century Puerto Rico.” Diplomatic History 25, no. 2 (2001): 186. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24913753.

- Ibid., 186.

- Ibid., 187.

- Ruben B. Martinez. “Puerto Rico’s Decolonization,” Foreign Affairs 76, no. 6 (November 1, 1997): 105. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.loyno.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edshol&AN=edshol.hein.journals.fora76.115&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- “Blanton Winship”. Wikipedia, Last Modified December 1, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blanton_Winship#

- Dennis Merrill. “Negotiating Cold War Paradise: U.S. Tourism, Economic Planning, and Cultural Modernity in Twentieth-Century Puerto Rico.” Diplomatic History 25, no. 2 (2001): 187. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24913753.

- Merrill, “Negotiating Cold War Paradise: U.S. Tourism, Economic Planning, and Cultural Modernity in Twentieth-Century Puerto Rico,” 189.

- Ibid., 188.

- Ibid., 188-189.

- Ibid.

- Martin J. Collo. “The Legislative History of Colonialism: Puerto Rico and the United States Congress, 1950 to 1990.” Journal of Third World Studies 13, no. 1 (April 1, 1996): 216. doi:10.2307/45197659.

- Dennis Merrill. “Negotiating Cold War Paradise: U.S. Tourism, Economic Planning, and Cultural Modernity in Twentieth-Century Puerto Rico.” Diplomatic History 25, no. 2 (2001): 191. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24913753.

- Pedro A. Caban. “Industrial Transformation and Labour Relations in Puerto Rico: From ‘Operation Bootstrap’ to the 1970s,” Journal of Latin American Studies 21, no. 3 (October 1, 1989): 560. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.loyno.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.156962&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- Ibid.

- Dennis Merrill, Negotiating Paradise : U.S. Tourism and Empire in Twentieth-Century Latin America (UNiversity of North Carolina Press), 186.

- Dennis Merrill. “Negotiating Cold War Paradise: U.S. Tourism, Economic Planning, and Cultural Modernity in Twentieth-Century Puerto Rico.” Diplomatic History 25, no. 2 (2001): 189. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24913753.

- Ibid., 194.

- Ibid., 192

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 197.

- Ibid.

- Arthur J. Mann. “Economic Development, Income Distribution, and Real Income Levels: Puerto Rico, 1953-1977.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 33, no. 3 (April 1, 1985): 487. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.loyno.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsjsr&AN=edsjsr.1153948&site=eds-live&scope=site.

- “La Mallorquina”, Wikipedia, Last modified May 24, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Mallorquina

- “La Mallorquina”, Discover Puerto Rico, accessed December 10, 2021, https://www.discoverpuertorico.com/profile/la-mallorquina/3792.

- Cuadra Ortiz, Miguel Cruz, and Russ Davidson, Eating Puerto Rico : A History of Food, Culture, and Identity (North Carolina Press: 2013), 214.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.