Setting the Stage

During the day, life dragged on heavily through the streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown residents went by with the bustles and laborious strides that counted the passing hours. But, as the sun went down, the streets filled with all walks of life, for in the late 1930s, nightlife in Chinatown was like no other. The hours were endless, and the pleasures infinite.

During this time, a booming number of nightclubs were being built throughout Chinatown, and standing at the forefront was the Forbidden City. Proclaimed as San Francisco’s most glamourous show and “the world’s most famous nightclub,” promising customers a dinner, dance, and show saturated with the spectacle of the Chinese culture and exotic allure that accompanied it. On the surface, the Forbidden City served as just a nightclub where performers played shows and customers had countless drinks. In its depths, however, was the cultivation of this particular style and cuisine that contributed to the emergence of Chinese-American culture as we know it.

Specifically, these main influencing factors can be found in the performances, shows, and the interior design of the nightclub, as can the contents of the menu, which featured dishes like chop suey and chow mein. These elements are known to not be original aspects of either Chinese social or culinary practices, and were instead adopted through “Americanizing” some pre-existing elements to be marketable in the American setting. To fully trace this transition, we must start at its beginning.

The Wonders of Forbidden City

During the 1930s, restaurants in Chinatown catered primarily to occidental tastes and began to incorporate live music into their program. One of the first to do so was Charlie Low; on December 22, 1938, Nevada’s small store owners’ son opened the Forbidden City around the corner on the second floor of 373 Sutter Street. Low did this following the success of the Chinese Village, which he opened two years prior.

Named after the imperial court and playing into the double entendre, Forbidden City sat on the outskirts of San Fransico’s Chinatown, opening its doors to the white masses that grew curious of the exotic splendor that it promised. The primary customers were made up of white servicemen from WWII and Hollywood celebrities — who were desperate to witness the “oriental” performance promised in magazine spreads — in addition to the small percentage of Asian American locals and tourists. This grouping composed the nightly audience of about 2,000 individuals, who would attend the bar and watch the dinner floor show. Chinese-American performers would entertain each night folks with a dazzling three-ring circus with singers, chorus lines, dance teams, and acrobats. Though most of the workers were Chinese American, the staff also included Filipino, Japanese, and Korean Americans as well.

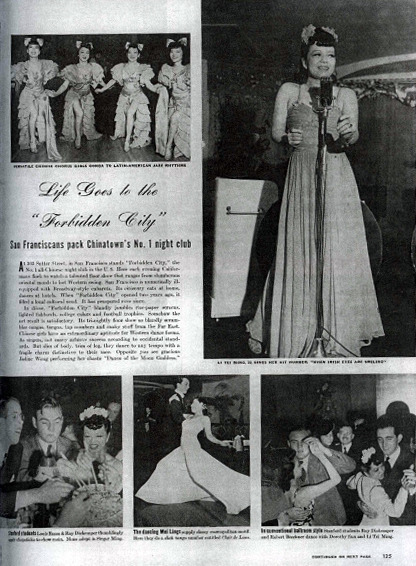

Accounts of Forbidden City go as follows: a jacketed doorman would greet visitors outside before drawing them into the club’s grand interior, filled with its rich tapestries and Mandarin-collared bartenders. From where the visitors would sit, they would be able a large gold Buddha looking down on them from the bandstand.1 In Life magazine’s 3-page spread dedicated to the Forbidden City, it states: “in decor, ‘Forbidden City’ blandly jumbles rice-paper screens, lighted fishbowls, college colors, and football trophies. Somehow the net result is satisfactory. Its tri-nightly floor shows blandly scrambles congas, tangos, tap numbers, and snaky stuff from the Far East. Chinese girls have an extraordinary aptitude for Western dance forms. As singers, not many achieve success according to occidental standards. But slim of body, trim of leg, they dance to any tempo with a fragile charm distinctive to their race.” 2

Lee, Coby. Coby Lee Dancing at Forbidden City. n.d.

https://datebook.sfchronicle.com/dance/coby-yee-iconic-exotic-dancer-and-owner-of-forbidden-city-dies-at-93

It is not without notice that much of this plays on the expectations of white customers. The performers would play into the exotica fantasies and foreign theatrics expected in many cases. These grand rooms with tables, a dance floor, and a cabaret show promised their clientele a “taste of China,” but really, it was more China-by-way-of-Hollywood. The facades and interiors of places like Forbidden City — the Chinese Sky room, Club Mandalay, the Kubla Khan, the Lion’s Den, Club Shanghai — were done up in Western stereotypes of Chinese culture, from the pagoda roofs to the rice-paper screens and lanterns.

Diners could order familiar nightclub-staples like steak and potatoes while Chinese American chorus girls would make their entrance in modest cheongsams, quickly discarded to reveal sexy burlesque costumes underneath. Elegant chanteuses sang popular American ballads in curve-hugging evening gowns, and dapper men sang and danced in tuxes and top hats.3 It is through such experiences that development of social aspects of Chinese American culture. Most performers stood in limbo, keeping Chinese and other Asian traditions while adding “Americanized” twists. As much could be seen with the branding of Asian American performers to well known American artists, such as Larry Ching, the “Chinese Frank Sinatra,” and Frances Quan Chun, singer billed as the “Chinese Frances Langford”.

The Menu

http://menus.nypl.org/menus/27218/explore

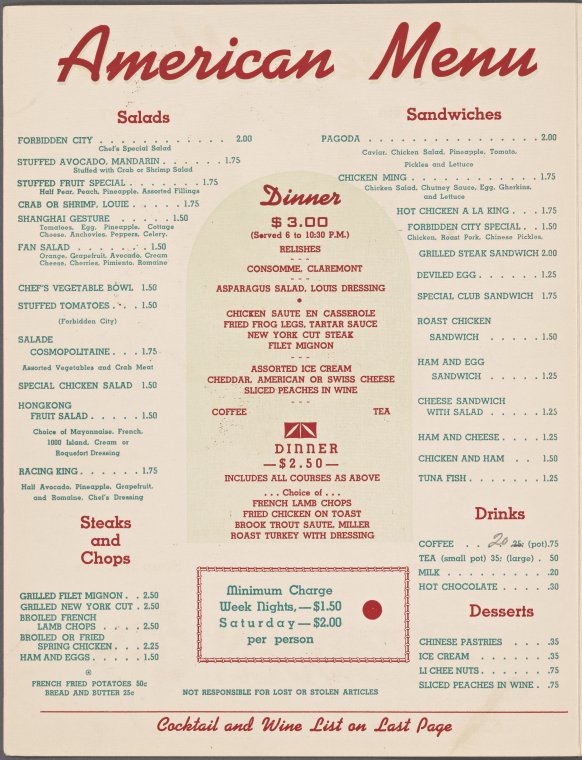

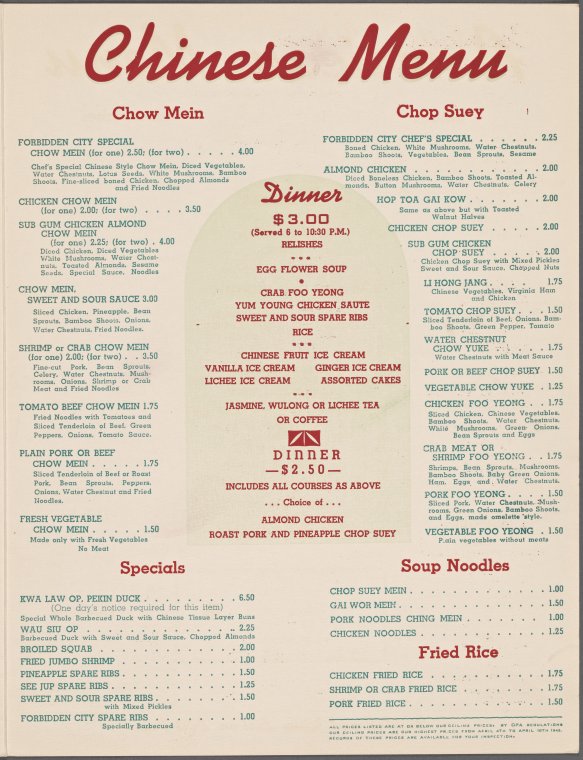

It was standard from 1920 to 1940s for Chinese restaurants to have an extensive list of American dishes and an all-English menu. Forbidden City did not stray away from this practice, including an American menu on one side — including salads, sandwiches, steaks, chops, and desserts like ice cream — with domestic ingredients familiar to American customers. On the other side was the Chinese menu; there were assortments of chow mein, chop suey, egg foo young, fried rice, soup noodles, and house specials. Much of the food was not authentic to Chinese cuisine, but by promoting their dinner menus alongside the shows, Chinese food (this new form of it, in any case) became popular in America.4

In doing so, Forbidden City drew crowds of Americans from all across the social strata, and for reasons not centering around the entertainment line-up. On Saturday nights, Forbidden City would pack the house with either one-dollar dinners or one dollar and fifty cent meals. While the dishes offered were far from the authentic cuisine of China, many of the items included were staples of Chinese American cuisine. The trickery seen in the Forbidden City’s performances reflected in the courses offered: fried rice, chop suey, and chow mein. Though patrons at that time expected authentic Chinese food or even an exoticized version of the cuisine, the version they received catered to flavors their taste buds were already used to. “Even though Americans like the Chinese food they now are getting, it must be admitted that most Chinese restaurants are producing a type of food that is not really Chinese: It is more properly called ‘Chinese-American,’ that is, a type of food, based on Chinese cooking, that has been designed for Americans.” 5

A critical note on the menu is the categorization of “the big three” dishes that made their way into all Chinese restaurants during this time (and later became staples of Chinese-American cuisine): chop suey, chow mein, and egg foo young. The first, chop suey, is like most of the food found in Chinese restaurants at the time. At its core, it is a cheap and convenient dish composed of meat variations of either chicken, fish, beef, shrimp, or pork and eggs, combined and cooked quickly with vegetables such as bean sprouts, celery, mushrooms, bamboo shoots, water chestnuts, and celery. The second, chow mein, is a stir-fried dish consisting of noodles, meat (chicken is most common, but pork, beef, shrimp, or tofu sometimes being substituted), onions, and celery. In preparing chow mein for American tastes, many restaurants altered the process of cooking a traditional noodle dish: while chow mein in China is made by boiling and then stir-frying long noodles, the altered recipe makes it so the noodles are only inch-length (making it suitable for forks rather than chopsticks) before being fried and marinated in sauce. This makes it so the mein (noodle) still has a more intensely crisp texture when the dish is served. Lastly, egg foo young is a Chinese omelet filled with vegetables, pork, and shrimp covered with a sauce.

These three courses remain a staple that circulates through numerous Chinese restaurants due to their inexpensive and convenient nature, remaining both accessible to American palates as well as profitable. In addition, dishes such as chop suey, chow mein, and fried rice were necessary for many restauranteurs to please the American palate. Much like the emergence of American Chinese dishes, Forbidden City worked the same it both through a need for space and profit as well as the consequences of Americanization built the silhouettes of Chinese American culture.

Last Thoughts

Forbidden City laid out a path for Chinese Americans of the newer generation to express, create, and entertain through an amalgamation of Chinese culture and American culture — both through social means but more specifically through a culinary outlets. Though both marketing and select performances hosted at the nightclub consisted of racist undertones that catered to xenophobic American perspectives, the existence of the Forbidden City still granted artists a space to perform and network. The Forbidden City certainly had its critics, but despite its flaws, it grew to not only become a popular social hub for performers and patrons alike, but also a historical landmark in Chinese American culture.

Written By: ayanac2411

Originally Published: December 16th, 2021 || Last Updated: May 30th, 2022

A part of Doc Studio’s History of Food in America Collection

Notes

- 1. East Meets West, Over Cocktails: A book and an exhibition recall vanished Chinese nightclubs Ito, Robert New York Times (1923-); Apr 13, 2014; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times pg. AR2 https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/13/arts/music/east-meets-west-over-cocktails.html

- 2. Ofanotherfashion. Of another fashion, February 1, 2011. https://ofanotherfashion.tumblr.com/post/3036052847/life-magazine-ran-an-article-on-charlie-lows.

- 3. Hix, Lisa. “Dreams of the Forbidden City: When Chinatown Nightclubs Beckoned Hollywood.” Beyond Chron, February 3, 2014. https://beyondchron.org/dreams-of-the-forbidden-city-when-chinatown-nightclubs-beckoned-hollywood/.

- 4. Spiller, Harley. (2004). Late Night in the Lion’s Den: Chinese Restaurant-Nightclubs in 1940s San Francisco. Gastronomica, 4(4), 94–101. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/gfc.2004.4.4.94

- 5. Shun Lu, & Fine, G. A. (1995). The Presentation of Ethnic Authenticity: Chinese Food as a Social Accomplishment. The Sociological Quarterly, 36(3), 535–553. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4120779

- Paul Chan and Kenneth Baker, How to Order a Real Chinese Meal (New York: Guild Books, 1976), 5.

- 6. Richard Wing, interview with the author, March 12, 2001.