The story of the Ruffino family traverses the entirety of the 600 block of St. Philip.

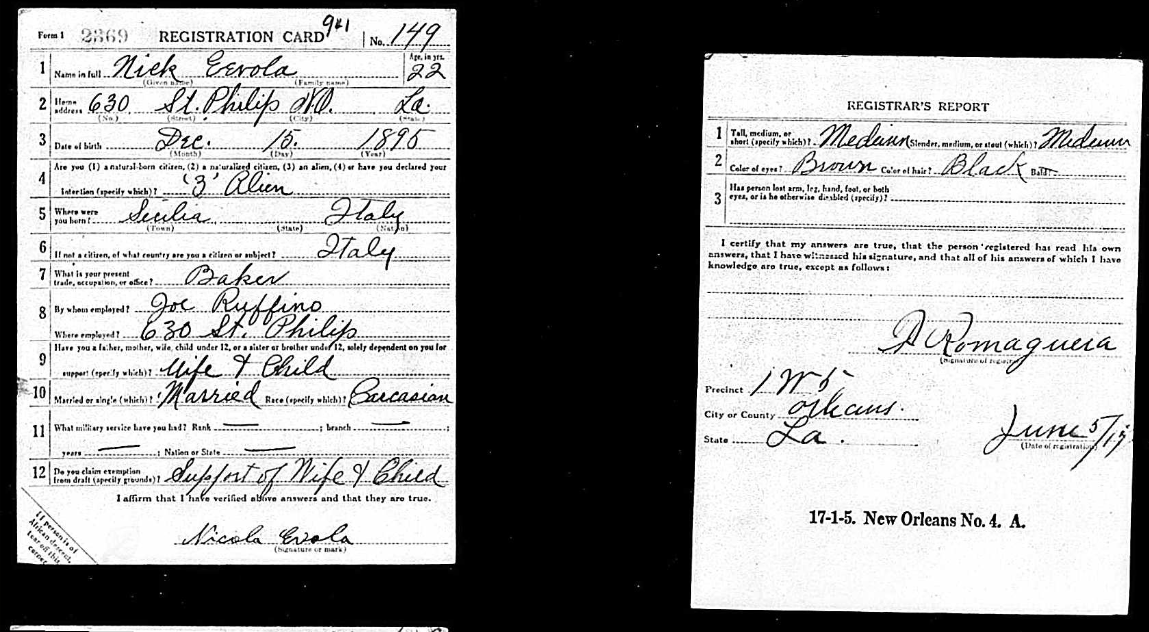

Giuseppe Ruffino, the head of the family, came to New Orleans from Cinisi Italy in 1892 with his wife Teresa. Together they had ten children all born in New Orleans. Giuseppe owned various properties in the Quarter. He first acquired the house 630 on St. Philip in 1919, his next purchase a year later was the 625 – 631 lot across the street, and his last holding on St. Philip was 628 in 1928. The family retained possession of these three properties until the late 1970s. With the purchase of the 625 lot, Giuseppe began the first of the Ruffino businesses—Ruffino’s Bakery. This bakery quickly became a staple in the French Quarter. His obituary in the Times-Picayune mentions Ruffino’s Bakery and its presence in the area. Another Times-Picayune article, this one from 1995, reproduced a picture of the entire Ruffino family taken in 1926 in front of the bakery. They call the bakery “a longtime Vieux Carre fixture.” If one wonders down this street today, the remnants of the bakery are present. Above the garage of the 625 house stands proudly in black raised letters against a light grey background, “Ruffino’s Bakery” and the dates 1907, 1923. However, the account of this bakery was not always a happy one.

625 St. Philip Street as it stands today.

Ruffino’s Bakery faced its own trials and tribulations throughout its existence. The Times-Picayune in 1921 discussed the health officials raids of downtown bakeries. Charges were filed by the superintendent of public health against Ruffino for food exposure to flies and dust as well as insanitary conditions. For Giuseppe, an act of kindness in 1927 led to a gruesome surprise the next morning. In mid-December Peter Perrett, a “homeless vagrant,” bidsanctuary from the brutal cold outside. Giuseppe opened the doors to his garage to the man for the night to protect him from the harsh elements. The next morning Giuseppe found Peter dead in the garage. The Times reported that officials claim the death of natural causes. Another tragedy occurred in 1931 when a fire started in the bakery and spread to the neighbors. Damages totaled to 6,350 dollars, only partially covered through insurance. The last great battle regarding the Bakery appeared in the Times-Picayune, the New Orleans Item, and the New Orleans State. These newspapers covered the argument between Giuseppe Ruffino and the National Recovery Administration. The New Orleans State edition provided this issue with the most real estate, employing quotes and providing background information. A blue eagle insignia in the window of an establishment represented affiliation with the NRA and accordance to its decrees. The charge against Ruffino’s Bakery is failure to compile with the agreement in regards to wages and hours and as a result the NRA demanded their insignia returned. Giuseppe claimed that his employees receive a minimum of 15 dollars a week and never work more than 40 hours a week. The outcome of this dispute is unknown. Each article only mentioned the argument once. While the bakery proved central to the Ruffino family, Giuseppe’s narrative moved beyond those four walls.

Giuseppe Ruffino’s story existed outside of the bakery.

There are three separate cases involving Giuseppe, alcohol, and prohibition covered by the Times-Picayune and the New Orleans Item. The verdicts regarding violation of prohibition laws included 60 days “in the hall,” 60 day house detention, and one case sent to trial with an unknown verdict. The one article proclaimed, “Father Goes to Jail for His Two Sons.” The family unit was essential to Giuseppe Ruffino–demonstratedby the close proximity of his family to each other and how each member helps in the family business. By the time Giuseppe passed, he was the proud grandfather to 20 children, and a great-grandfather to nine. His wife Teresa is never mentioned in newspapers outside of her obituary. His ten children carried on his legacy in the French Quarter.

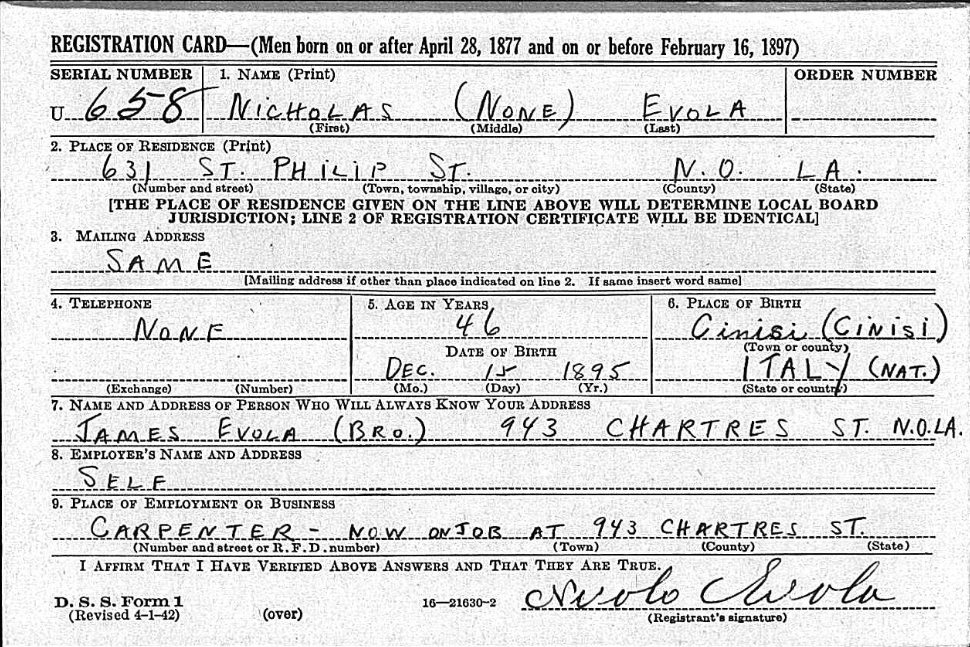

Giuseppe’s daughter Stefana (Fanny) continued expanding the family’s relationship to food culture through her own family. Nicolo (Nick) Evola married Stefana (Fanny) Ruffino June 24, 1915. At the time of this holy union, they were both 18. They proceeded to live at 630 St. Philip with her family and work in the bakery. His World War I Draft Card provided a physical description that painted Nicolo as a man with medium height and build with brown eyes and black hair. His World War II Draft Card disclosed that he moved to 631 St. Philip and his brother, Giacomo Evola, resided at 943 Chartres. His time spent working with his father-in-law in Ruffino’s Bakery provided Nicolo with the necessary knowledge required to run his own bakery, United Bakery on 1325 St. Bernard. Nicolo, like Giuseppe, had problems with the health department. The New Orleans State reported in 1949 that the health department forced closure on the bakery due to violations. The Times-Picayune divulged more information, listing the violations: “unscreened windows, dirty walks, inadequate washing facilities, and lack of board of health permit.” Years later, in 1963 both the Times and the Orleans States-Item disclosed a story regarding a robbery of Nicolo’s bakery. Mrs. Dominick LoGiudice, his daughter, stood behind the counter working when at 6:50 p.m. a man wearing a stocking that obscured his facial features entered the shop wielding a pistol. This “bandit” demanded that she open the register and hand over all of the cash. She bravely refused and told him to do it himself, which led to him aggressively opening the register and relieving the business of 25 dollars. Thankfully no one received any injuries and the police investigated the incident. The outcome of their investigation remains elusive. The relation of United Bakery with the Quarter embodied the relationship between food and the community.

The story of United Bakery highlights important aspects and themes of Creole Italians.

One of these themes is the importance of the family unit. Nicolo first worked in his father-in-law’s bakery. The two families lived in close proximity to each other, remaining on the same block of St. Philip. This trend of famgilia work relationship continued when Nicolo opened his own bakery in which his one of his daughters worked, even after her marriage. Mrs. Dominick LoGiudice is often mentioned in the newspaper articles referring to United Bakery. One such occasion appeared in the Times-Picayune in 1959 regarding the United Bakery and St. Joseph’s altar—another Creole Italian tradition continued in New Orleans. In recognition of St. Joseph’s intercession during a time of starvation and suffering, Sicilians celebrate his feast day, March 18, with elaborate altars full of symbolism and pastries. This tradition of St. Joseph’s Altars calls for the construction of three-tiered altars, often in the living room of a home. The altar houses a statue of the Saint surrounded by fresh flowers and candles while the rest of the altar is full of breads, fruits, and cakes. As a bakery, March kept them busy and full of special requests. They baked bread in any shape, even beards, hands, feet, canes, palm leaves, crosses, four-leaf clovers, knots, half-moons, crowns, and even Christ on the cross. Their delicious Italian bread, with all its shapes, was highly sought after. The time of Dominick’s quote marked United Bakery’s 50th year with St. Joseph. United Bakery’s longevity paralleled with Nicolo’s brother Giacomo’s corner grocery store.

Giacomo (James) Evola, Nicolo’s brother, also married into the Ruffino family. He married Stefana’s younger sister Jennie. Giacomo came to New Orleans about ten years after Nicolo. A passenger log describes Giacomo on its list. The vessel Atenea docked in New Orleans on May 5, 1928. Giacomo, listed as a seaman, was a literate 26 year old at 5’7’’ and 160 pounds. After his marriage to Jennie, he worked with his father-in-law and brother in Ruffino’s Bakery. Eventually, he left the baking business and opened a grocery store—Evola’s Food Market— in the ground floor of his residence, 637 St. Philip. This business rarely received any recognition in newspapers, but for the explicit mention of his wife and daughter’s help in running the business and another robbery. Someone stole 50 dollars and nine bottles of whiskey from Evola’s Market in 1956. This sentence was all the information discovered regarding the incident.It is unknown whether the police found the perpetrator or how the person committed the crime. Likewise, only minor details were found regarding Jennie Ruffino Evola. The Times-Picayune recorded the birth of their daughter, Agatha, in 1929 at French Hospital. Agatha eventually married and became Agatha Miller. Together they have a child Jenan. When Agatha is mentioned again, it was as Agatha Frisard. The reasoning for her second marriage remains unclear. Earle and Agatha have three sons together: Earle, John, and Michael. At the time of Jennie’s death in 1995, she was the proud grandmother of four and a great-grandmother to seven children. Jennie and Stefana’s narrative followed along similar patterns and trends, ones that their sister Susana did not.

Susana (Susan) Ruffino departed from the trend her sisters established. She married Salvatore (Sam) Curcuru. The date of their marriage remained elusive. Salvatore’s occupation according to his obituary, was as a barber for the Montelone Hotel. They resided at 724 Washington Ave at the time of his passing in 1963. Together, Salvatore and Susana had four children: Teresa, who married Lawerence Stornioio, Virginia, wed to Victor Gorgone, Philip, and Joseph. This family’s chronicle demonstrated that a connection to the food industry was not a requirement for the Creole Itlaian narrative. Very little revealed itself regarding this small family unit during the research phase. Susana’s brother Francisco, however, lived a well documented life.

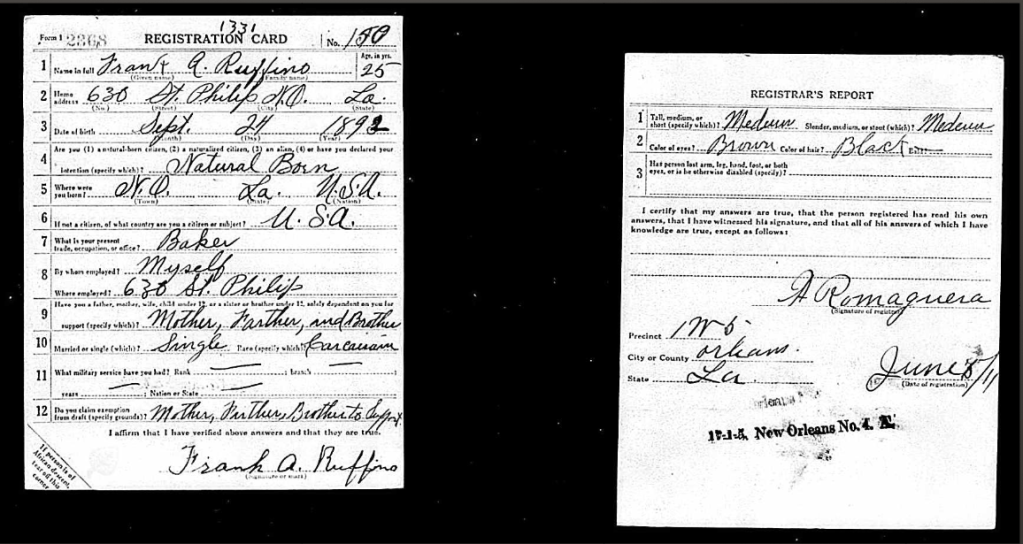

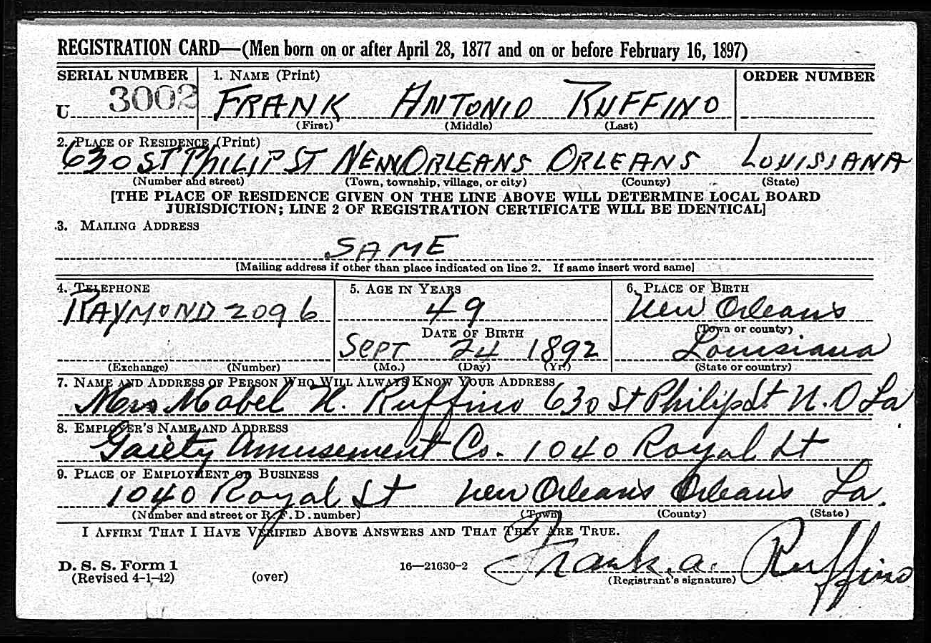

Francisco (Frank) Ruffino, the oldest of the Ruffino children, remained close to his family while also exploring his own interests. The earliest record discovered regarding Francisco was his World War I Draft Card. Written in 1917, it describes him as the main breadwinner in his family with his parents and siblings as dependents. Characterized as a young man with a medium height and build and brown eyes with black hair, Francisco worked as a baker at Ruffino’s Bakery. The following year he married Mattia (Mabel) Napoli. The Times-Picayune recorded this joyous event. Together they have five children–their son Charles passed away at the age of 15 in 1937.Francisco helped in the family Bakery, but shortly after the passing of his father, Giuseppe, he purchased a business around the corner, the Gaiety Theater. While Creole Italains experienced success and influenced the culture of the French Quarter, not all appreciated their presence. Many referred to Fransico’s Theater as the “Garlic Theater” because it was frequently full of Italians. Fransico however, remained a proud owner, and his name often appeared in conjunction with Chest Community showing certainty movies. Francisco’s World War II Draft Card listed his occupation as operator of Gaiety Amusement Company on 1040 Royal in 1941. While his employment changed, his address remained the same—630 St. Philip. Mattia’s name appeared in relation to her marriage record and death index. According to her obituary in the Times-Picayune, she died in 1974 a grandmother to nine and a great-grandmother to three. Francisco and Mattia’s family stayed near the Ruffino family through their residence on St. Philip and their place of employment on Royal even while their business endeavors strayed. Fransico’s younger brother Victor likewise continued to reside on the same block but he also aligned his business interests with the family’s.

The life of Victor Ruffino aligned with the typical Creole Italian narrative and its connection to food.

Victor is the second to youngest of the Ruffino’s. As such, by the time he began working Giuseppe retired from Ruffino’s Bakery, and Ruffino’s Grocery on 608-610 Dauphine became the main focus of the family. Giuseppe purchased the property on which the store stood in 1925. Not much was uncoveredregarding the Grocery store during research. Victor distanced himself from the grocery store but remained in the food industry. He opened a bar, Vic’s Place, the location of which moved but eventually landed on 626 St. Philip. The earliest mention of Vic’s Place is in the Times-Picayune in 1946 applying to the Collector of Revenue for a permit to sell alcohol. For the next two decades, Vic’s Place appeared in the Times applying for various alcohol permits in numerous location, creating a picture of movement. The last permit discovered listed the address of 626 St. Philip. Aside from an article in the New Orleans Item about a man named “The Duke,” Vic’s Place stayed out of the newspapers. Even his personal life remained clear of newspapers with few exceptions. Victor married Ione Barham and together they had five children: Patricia, wed to Leonardo Sweeney, Julie, married to Leonardo Palazzo, Cynthia, Rudy, and Victor Jr.. The Times-Picayune announced Julie’s engagement to Leonardo Palazzo in 1959. Their October weddings took place in St. Mary’s Italian Church—another important feature of Creole Italian life.They feature pictures in both editions mentioning the event; the announcement is a headshot with the classic 1960s tall and puffy hairstyle, and the recounting of the wedding depicted the glowing bride in her long sleeved ballgown wedding dress. Victor’s narrative intertwined with the food industry seamlessly, first through his employment at his family’s grocery store and then as proprietor of a bar. Vincent Ruffino. The youngest of the Ruffino family, mirrored his brother Victor by weaving his narrative with food.

Vincent followed in the footsteps of his siblings, earning his living in the food industry. He married in 1937 to Anna Tamburello and together this duo opened Ruffino’s Italian Restaurant in 1961 at 625 St. Philip—where Ruffino’s Bakery once flourished under Giuseppe. The Orleans State-Item mentioned the Grand Opening on three separate occasions. This restaurant and lounge had indoor parking with an attendant—yes this was in the French Quarter! Vincent and Anna were a team, the Times-Picayune proclaimed that Vincent was “ably assisted in the operations by Anna.” This team worked well together with Vincent in the front and face of the restaurant and Anna, the wonderful cook, in the kitchen creating “masterpieces of culinary art.” Their specialties included: baked lasagne, veal scalloppini, chicken cacciatore, and pizza. Ruffino’s quickly became “a charming hideaway” and well loved neighborhood restaurant. There are numerous ads in the papers regarding daily specials and great deals. Similar to Ruffino’s Bakery, Ruffino’s Restaurant experienced its own woes with its successes. Both the Times-Picayune and the Orleans State-Item vividly described a robbery of the Bar side of the restaurant in 1961. Two men on Tuesday at 12 a.m, waltzed into Ruffino’s Bar where five other patrons were enjoying themselves. One man walked up to the bar and slyly drew attention to his armed friend in the doorway. The man then demanded money and escaped with a hundred dollars without any of the patrons noticing the danger. This team robbed two other restaurants together. Next to the article, the Times-Picayune featured a sketch of one of the bandits. Vincent left a legacy through the Ruffino’s Italian Restaurant, three children (Mrs. Leonard Jones, Charles, and Frank), and six grandchildren (Leonard, Michael, Charles, Vincent, Charlene, and UNKNOWN). Vincent is the last of the Ruffino’s with such a rich narrative connected to employment and family businesses.

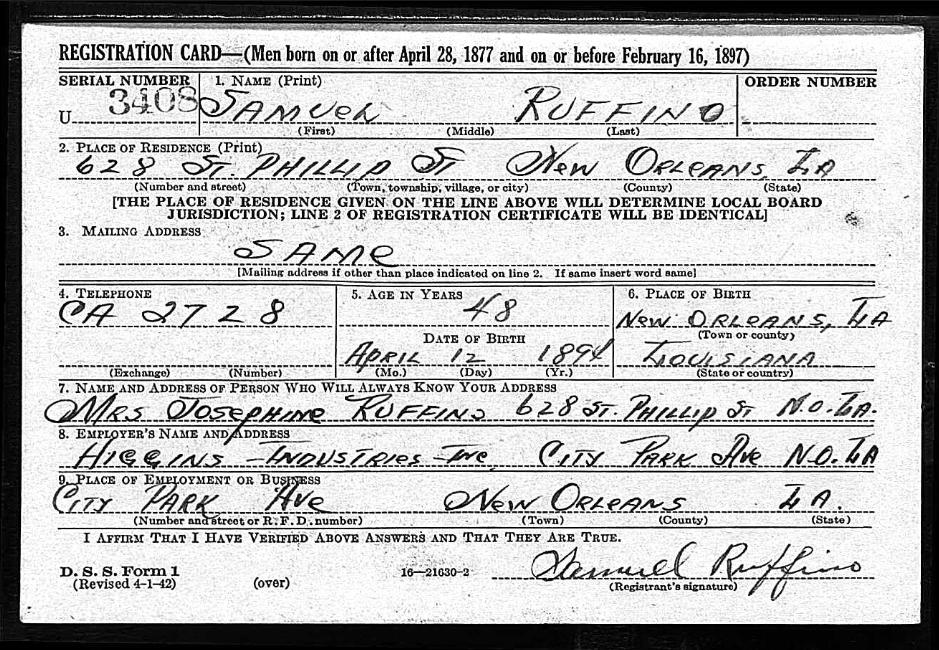

Information known regarding Salvador (Samuel) Ruffino shifts gears and focuses more on personal account. Salvador’s World War I Draft Card described him as a man, 23, of a medium height and slender build, complimented with black eyes and hair. His employment was as a baker at his father’s bakery. Between World War I and World War II he married Joshpine Conchilla and by the time of the Second World War he celebrated his 23rd wedding anniversary and was father to Mary Jane. When Salvador filed his second drat card in 1942, his residency moved one house down to 628 St. Philip. No longer did he work for the family however, but rather as an employee of Higgins Industries. The last article of information related to Salvador was his obituary. Here it was discoveredthat Josephine passed before Salvador and he remarried Marina Lorenzana, a second marriage for her as well. He became a step-father to Marina Maven and father to Frank, Joseph, Mrs. Joseph Assunto, and Mrs. Joseph Falo. At the time of his death, he was grandfather to 15 children and great-grandfather to another two children. With this, Joseph concludes this chapter of history on St.Philip with the last information regarding the Ruffino family.

Telling the story of the working class population provides a deeper understanding of the culture, tradition, and time period. It is not a simple and easy task, since most records focus on rulers and prominent business figures. As such sometimes there are numerous sources, like with Giuseppe and Vincent Ruffino, and other times there is a serious lack of information, as seen with Joseph Jr., Benny, and Dominick Ruffino. However, the sources discovered through labor intensive research paint a distinctive picture of the Ruffino family. The legacy of the Ruffino family is one closely connected to the Creole Italian narrative: family and food.

A Times-Picayune article from 1964 expressed this phenomenon:

IT BEGAN WAY BACK IN 1890 WHEN SIGNOR GIUSEPPE RUFFINO AND HIS WIFE TERESA LANDED IN NEW ORLEANS AND IMMEDIATELY LOCATED THEMSELVES INT HE 600 BLOCK OF ST. PHILIP…TODAY, 73 LATER, SIX (OF THEIR TEN) OFFSPRINGS EITHER LIVE OR CONDUCT THEIR OWN BUSINESS IN THE SAME 600 BLOCK OF ST. PHILIP…THE RUFFINO’S TODAY LAY CLAIM TO BEING ONE OF THE LARGEST ITALO-AMERICAN FAMILIES IN NEW ORLEANS, ALMOST CERTAINLY THE LARGEST AND CLOSEST RESIDING FAMILIES IN THE FRENCH QUARTER.

Once Giuseppe Ruffino established his bakery, all of his children and majority of their spouses worked together; most even lived together in the same house. Eventually, each child moved into their own houses with their families on the same block. An assortment of the Ruffino family worked in the food industry: Nicolo and Stefana owned the United Bakery, Giacomo and Jennie were the proprietors of the Evola Food Market, Victor and Ione retained Ruffino’s Grocery and Vic’s Place, and Vincent and Anna controlled Ruffino’s Italian Restaurant and Bar. The exceptions are Salvatore Curcuru, married to Susana, who worked as a barber and Francisco, wed to Mattia, who owned Gaiety Theater. The occupations of Joseph Jr., Salvador, Benny, and Dominick are unknown. This family’s chronicle concentrated on business endeavors; meanwhile, the Greco family’s account fixated on the personal.

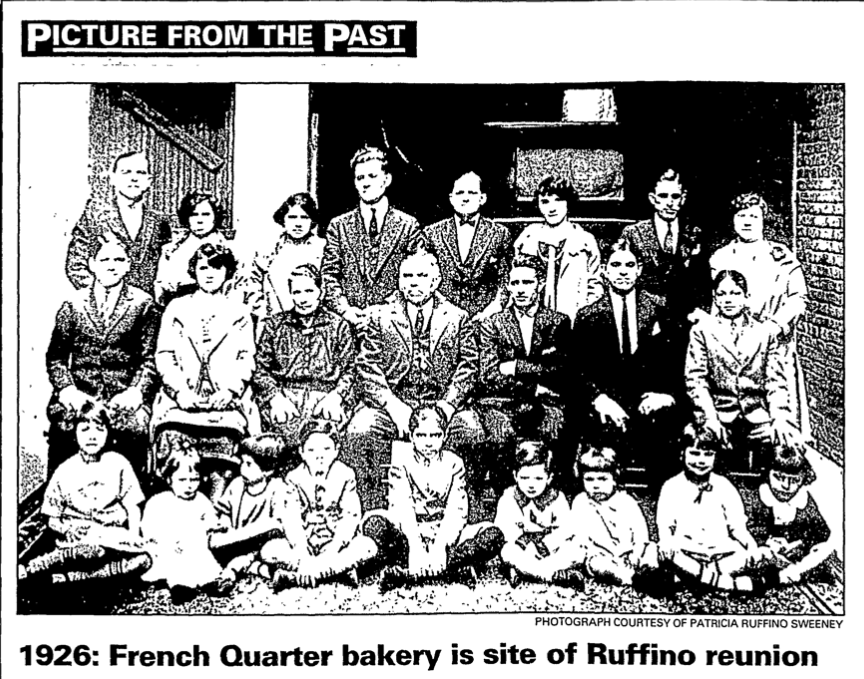

Corner of 600 Block of St. Philip, 1000 Royal.

Planbook Plan

View of St. Philip

One thought