First, A Quick History Lesson:

Up until 1871, much of Eastern New Hampshire hadn’t caught on to the railroad phenomenon that was taking America by storm, but transportation both for cargo and for people soon accelerated and became far more accessible to the general public. For the Kearsarge House in North Conway, New Hampshire, this meant a significant increase in visitors over a short period of time, and it is in the middle of this period transformation that our menu comes.

The Kearsarge House was started by Samuel W. Thompson in 1837 when he began inviting guests to stay in his house. This man oversaw the mail service for his little town in the White Mountains, delivering mail on horseback for quite a long time. Even as he did all of this, he also worked as an ambassador for North Conway, working hard to organize a stagecoach line from Portland, Maine to another nearby small town (Carroll). His ultimate plan, fully realized in 1840, was to make a stagecoach line that connected the end of the Portland-Carroll line, linking up North Conway with many choice destinations, including a large hotel known as the Glen House. This brought even more people to North Conway than ever before, and Thompson had even more guests to house. Even as he micromanaged this line and his budding hotel, in 1850 he also recruited artists to work on selections of paintings promoting the White Mountains where North Conway resided. That’s when the fabled year 1871 hit, and the Portland and Ogdensburg Railroad (more commonly referred to as simply the Eastern Railroad) was finished. This railroad connected Portland, Maine with Carroll, New Hampshire and with it came a lot of hungry, weary travelers. (Conway Daily Sun, 9/15/2014)

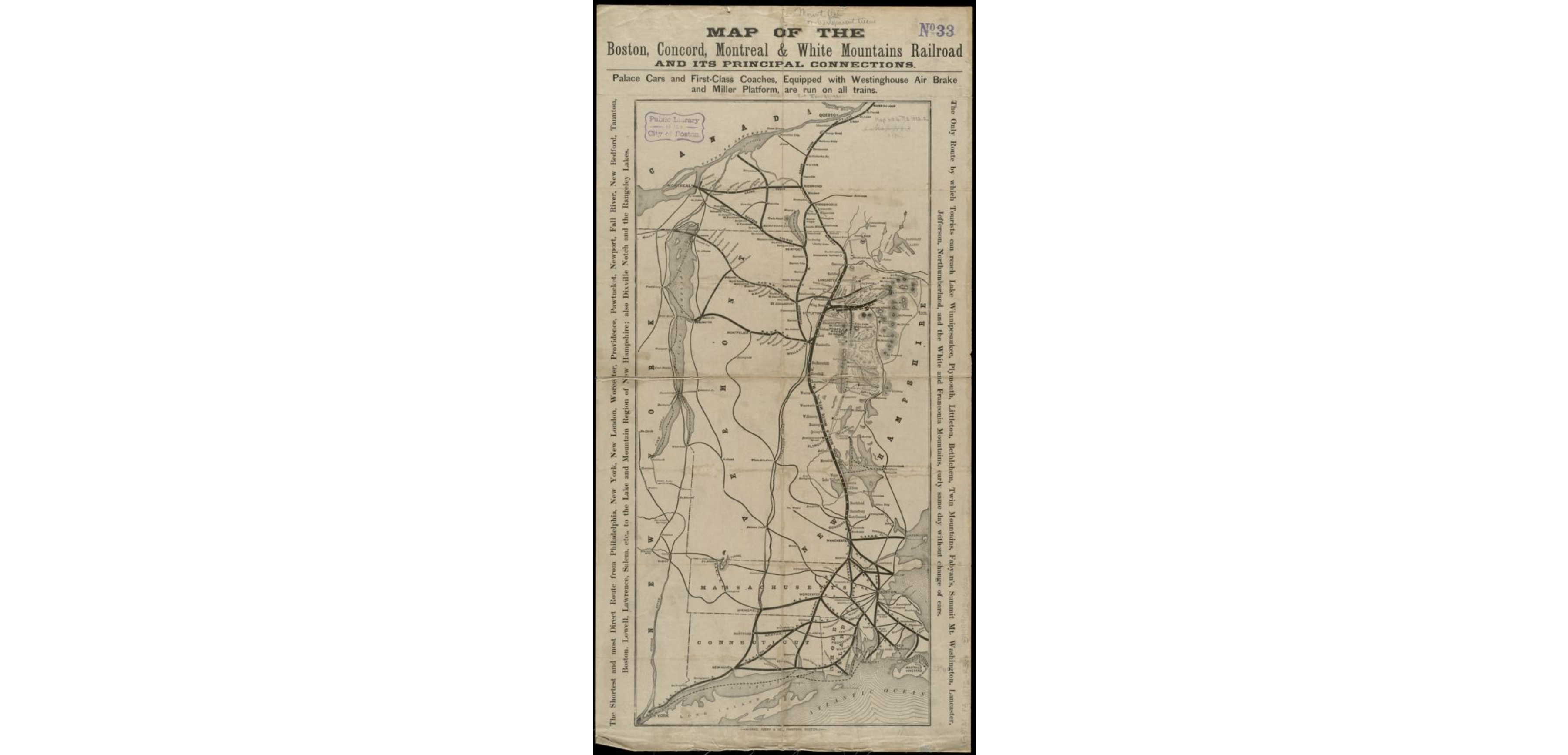

With such a huge influx of people on top of the pre-existing stage line, Thompson greatly upsized his house, transforming it into the beautiful Kearsarge House that stood for many years. This influx only greatened when the Boston, Concord, and Montreal Railway connected up with the Portland and Ogdensburg Railroad in 1875. It could house up to 300 guests, most of them from far away, and that meant that at any given time there were a lot of hungry mouths to feed. So, how did they feed them? What did they feed them with? How did they work to please as many palates as possible? And how did the Kearsarge House stand out amongst the other hotels on the same line and in the same area? Let’s find out!

A Menu of Similarities and Differences

The Kearsarge House, like any respectable hotel of its era, also acted as a restaurant. It is assumed that, like other hotels, it had a different menu each week, but it’s to be expected that most things stayed on the menu all year round. The most interesting thing about looking at menus from different eras is the stark differences and surprising familiar faces in the menus of today and the menus of yesterday. The same can be said about the Kearsarge House’s menu as well, which is depicted below.

You’ll notice right away that, similarly to menus of today, each kind of food is portioned off into sections, such as Sweets, Cold Dishes, etc. Unlike a lot of typical restaurants today, however, each section here is placed in a specific order. The hotel cook staff would serve copious amounts of food in what appears to be a Ten-course meal, each course having all the foods listed placed on the table as options for the customer to eat. This style, known as table d’hôte, was the “American style table”. This was a smart way to strike at almost everyone’s palate: no matter what kind of food people enjoyed or disliked, there’s always bound to be at least a few things that they would like on the menu.

It’s very possible that, barring any sort of cultural differences, many people today could find one if not many things on this menu that they would recognize and enjoy. Tomato soup, corned beef, onions, almonds: all these things are common foods even now. But what about the foods that we don’t eat today? What is Webster Pudding? What about Washington Pie? And what in the world is in White Mountain Cake? It’s time to jump into the foods of the past!

Webster Pudding

Mrs. Putnam’s Receipt Book and Young Housekeeper’s Assistant, a book originally written in 1858 by Mrs. E. Putnam, is a book full of recipes. As the book’s preface states, these recipes were intended for her daughters, but Mrs. Putnam eventually realized that they could be useful to other people as well. Officially published in 1867, the preface also claims three things about the recipes in the book: that the author has tried and liked them, that there are enough recipes to meet the wants of a family, and that they focus on providing the most food at the cheapest expense. This last part is crucially important, and I’ll explain why later. For now, I’ll discuss the Webster Pudding recipe found in this cookbook.

Like many other recipes at this time, very little detail is given about to actually prepare the food once the ingredients have been gathered. At the very least the measurements of ingredients are given (minus salt), and most of the ingredients are easily recognizable. However, there are three things that stand out as foreign are these: “soft as pound cake”, “cold sauce”, and the ingredient “saleratus”. The second and third one I can give an answer for: the first one shows that this recipe is meant for people who already do a lot of baking. The cold sauce that Mrs. Putnam refers to here is another recipe listed just below Webster Pudding. It’s a very simple sauce that is meant to add a little fruity flavor to one’s Webster Pudding.

Saleratus, on the other hand, isn’t as easy to identify since something like that doesn’t exist today. Or does it? As it turns out, Saleratus was a product invented in Europe as a leavening chemical. It wasn’t horribly reliable and was very expensive for Americans to import, so in 1846 American entrepreneurs Dr. Austin Church and John Dwight created their own version they called “Dwight’s Saleratus”. They made it slightly differently, however, and what they invented eventually became known as Baking Soda! So this ingredient totally exists today, just under a different name.

Washington Pie, and the Mrs. Putnam Conspiracy

The name “Washington Pie” isn’t exactly the most descriptive of names, so I had no idea what to expect from this strange pastry. I didn’t have to search very far to find a recipe for this pie: and who would have guessed it, but it’s in Mrs. Putnam’s cookbook as well!

This is definitely a fan-favorite of a someone with a sweet tooth. By looking at the recipe, it seems to a pie in name only, which is all but confirmed by the referral to it as a cake twice in the latter portion of the recipe. You actually need to bake two of these cakes in order to make the entire Washington Pie, putting some marmalade or jelly in the middle, almost like a sugary sandwich. Our friend saleratus shows up again, ever-helpful in the baking of pastries.

The most interesting thing to note here is that two of the most specific and foreign foods on the Kearsarge House’s menu seem to have their origins from Mrs. Putnam’s cookbook. It’s very possible, and I think likely, that they had this cookbook as a reference for a lot of the foods that they served there. Tripe, Corned Beef, Potatoes of all kinds: all of them can be found as recipes in this book. I’m not going to make the argument that they only used her recipes for everything: but I will argue that the cooks in the Kearsarge House used it as a sort of guideline for a good amount of their foods. Why? Because of what Mrs. Putnam herself expressed as one of the most important parts of the cookbook; she promoted recipes that serve a lot of people for little expense using inexpensive ingredients. And that is absolutely key for a hotel in the mountains trying to serve Ten-course meals for hungry tourists every single day. They needed the biggest bang for their buck, and—at least for the cook staff at the Kearsarge House—Mrs. Putnam’s Receipt Book and Young Housekeeper’s Assistant was the best guide to meet their client’s expectations.

White Mountain Cake

The Kearsarge House is located in the White Mountains, which is why I was immediately interested in its composition. Surely the name couldn’t be a coincidence: it must be some sort of local recipe to the White Mountain area. Unfortunately, the truth is far more boring than that: White Mountain Cake, which became big in 1872, was simply a triple-layer cake, and was called so because of its white frosting and its tallness. Popularized by the 1872 Appledore Cook Book, a White Mountain Cake was simply a Concord Cake that was baked in layers as opposed to all together. Concord Cake was named after Concord, New Hampshire, where it was first created. So while the recipe IS from the same state, the name “White Mountain Cake” is simply a coincidence since Concord isn’t very close to the White Mountains. The recipe can be seen below.

The Changes the Railroad Wrought

The arrival of the Railroad changed things in America forever: quick transportation for decent prices meant that the tourism industry boomed. With this boom came people, and with the people came different expectations of food. Because of this, there existed an implicit standard that hotels on the various stops of the railroad had to comply to, and thusly menus from this era and form this area look notedly similar. The Kearsarge’s 1873 menu is depicted again below for reference and as a general example.

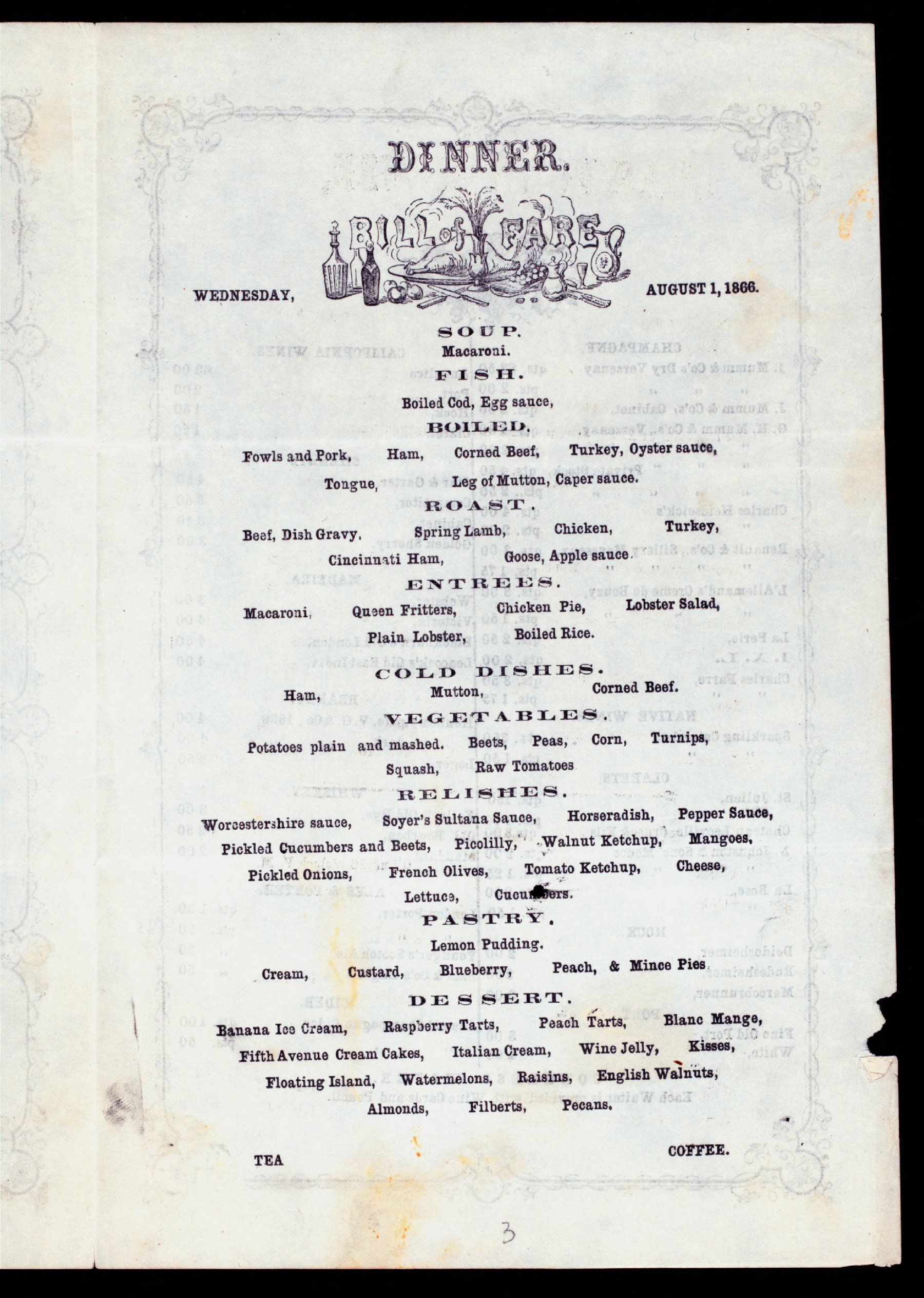

There were many stops on the Eastern Railroad, and because of this there were other hotels as well. Just as an experiment, I decided to look over the menu from the nearby Crawford House to compare and contrast the foods they offered around the same time. This menu is from a little earlier: 1866.

The similarities are pretty easy to spot—Almonds, Floating Islands (a kind of pudding), Corned Beef, Mutton, Potatoes, Macaroni, Custard, Fowl and Pork, Blueberry Pies—the list goes on and on. These menus are even from very similar times of the year: August 9th for the Kearsarge House and August 1st for the Crawford House. This means that similar things were in season in both years and brings these menus even closer together.

There are, however, some differences that are worth pointing out. As one would expect, White Mountain Cake isn’t on the menu, since it was popularized in 1872 and this Crawford House’s menu is from 1866. However, what’s more interesting is the fish offered at each hotel.

Instead of Boiled Salmon and Baked Halibut, like the Kearsarge House, the Crawford House only offered one kind of fish: cod. This is interesting given that the same fish should have been in season, but as I did some more research, I found that this was not the case. In 1871, the United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries was created. This organization aimed to survey various locations to see what kinds of fish lived where, and how many of them lived there. This is important because in August of 1872, people were permitted to collect and fertilize salmon eggs, and they began shipping them from California to the East Coast. This allowed them to plant salmon in rivers and areas where salmon didn’t live before. By 1873, which is the year of the Kearsarge House menu, salmon would have been all the rage to people living on the East Coast who hadn’t had them before, and were most likely a must-have for hotels and restaurants in the area. This explains why the Crawford House didn’t have salmon as an option, but the Kearsarge House did.

The Past in the Present

For the final part of my analysis of this 19th-century menu, I have decided to prepare an item from the Kearsarge House’s menu: the Webster Pudding and its corresponding Cold Sauce.

The first thing that you’ll notice about these recipes is that they aren’t very descriptive about how to actually put the ingredients together once you have them all prepared. Getting the ingredients together was the easy part, though we were unable to find currants and were forced to replace them with raisins. Also, I’ll add a side note that I’m absolutely awful at cooking, a fact I won’t deny even on my best days.

No harm no foul, but without proper instructions on how exactly to “mix as soft as pound cake”, I simply dumped all of the ingredients into a mixing bowl and mixed them all together for a couple of minutes. The mixture smelled greatly of cinnamon and mixed a lot easier than I expected it to.

The next instruction called for the whole concoction to be steamed for two hours, and not quite sure of how to do so, I placed the mixture into a pot on the stove and placed the lid on top of it, letting the simmering stove cook the mixture and letting steam fill the pot. In a way, it was like cooking rice, which I have done before.

Every 15 minutes or so, I would lift the lid to stir the contents and release some of the pent-up steam. Eventually I realized that this 15-minute-long gap was too short and I was keeping the mixture too cold. I turned up the heat slightly after an hour, instead stirring every 30 minutes. At the end of this process, the “pudding” looked something like this:

Whatever this is, it did NOT have the consistency of a pudding, instead looking and feeling more like a strange chili with far too many raisins in it. By this point the cinnamon smell was gone, replaced by the smell of cloves. It was then that I began to make the cold sauce, and also here where the lack of instructions started negatively impacting the whole operation. The recipe calls for butter and sugar to be “rubbed together” until all of it is white, but I had no context for how one was supposed to do this. Instead I simply mixed the butter and sugar together, and it went pretty terribly.

There was infinitely too much butter (even though I used the called amount!) and it did not mix well at all. After almost 30 minutes of stirring, I decided to give up mixing and juice the lemon. When I added the juice to the mixture, it actually began mixing together a lot better, and after I grated the lemon rind to get that zest in the mixture, the cold sauce finally started taking shape. However, due to unforeseen circumstances I had to leave my house after finishing the sauce, so I refrigerated both parts of the recipe to eat later.

So when the fateful hour arrived when I was to eat this recipe, I had absolutely no idea what it would even taste like. When I shoveled the stuff onto a small plate, I was somewhat impressed that the pudding actually had the consistency of pudding. The sauce was hard as a rock, so I warmed it up in the microwave for a few seconds. This is what it looked like:

If you think that looks unappetizing, you and I agree on that front. Going into my first taste of Mrs. Putnam’s recipe, I didn’t know if I would like it or not. And, well…

It was garbage. It was flaming hot garbage. A complete dumpster fire, if you will. I could barely muscle down three bites of this stuff! The cloves were too strong, there were altogether too many raisins, and the sauce was basically just butter and nothing else. Now, many factors could have led to this result. This recipe is from 1871, and so there’s a vast difference between the butter they used then and the butter they use today, for example. And it’s possible that currants really are preferred to raisins for a recipe like this. Maybe I failed to steam it correctly, or perhaps I put the ingredients in the wrong order. The most likely answer as to why my version of Mrs. Putnam’s Webster Pudding failed is because I suck at cooking and had absolutely no idea what I was doing. The sauce could have been good with a third of the butter, but other than that I guess it’s best that this recipe stays in the past; or, at the very least, goes into more capable hands than mine.

Oh wow, I just wrote a blog entry about this very menu for the Kearsarge House (my blog, The Road Backward, focuses on mainly Victorian and Edwardian history, and I feature old menus on Mondays). I was actually searching to find out precisely what these dishes are so I could do a follow-up post, but I’ll just link to this instead since you’ve already done all the work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great write-up , thank you.

The recipes you chose to explore exactly aligned with those I was curious about.

I discovered your blog because Tasting History posted the Kearsarge House menu, but now I can’t find the post in the middle of the night, LoL.

Your expression after tasting the pudding is hilarious. Thank you for posting.

Sincerely,

Beth

LikeLike