Leland University has had connections to Baptist institutions from its inception in 1870 to the time it closed in 1960. Specifically, the American Baptist Free Mission Society supported the construction of the school in 1870. In fact, Baptist connections were only strengthened with the guiding forces of the man for which the university was named, Mr. Holbrook Chamberlain. He was a shoe merchant from Brooklyn, NY, who was especially dedicated to providing quality education to recently freed slaves. While classes technically first began on January 4, 1871, they did not begin at Leland University as we know it. Classes were initially held in the Free Mission Baptist Church, which was then located on Common St.

What makes the history of Leland University not only interesting but crucially relevant is the context of it’s development. At the time, most schools only admitted African Americans who were free prior to the 13th Amendment. As such, freed slaves were still being unfairly treated since they did not have equal access to educational opportunities. However, on February 18, 1873, Congress passed legislation approving funding of $8,000 for the construction of buildings at Leland University in New Orleans.

Sometime after Congress passed the bill for funding, Leland purchased large property previously owned by the Ogden family, which was located on St. Charles Ave. & Audubon St. The following photographs pulled from the Robinson’s Atlas show the location of the school more accurately. The picture view of the area of district 6, and if you look closely, Leland has four plots marked off in the upper right-hand corner.

Mr. & Mrs. Chamberlain were key to the well-being and development of the institution, as they donated significant amounts of their own personal finances to help with purchasing the land as well as building the school. As such, the school took the name “Leland” in reverence and appreciation to the Chamberlain family, as Mrs. Chamberlain’s maiden name was Leland. Interestingly, this further demonstrates the institution’s connections with the Baptist faith, as Mrs. Chamberlain’s ancestor, Reverend John Leland, was a prominent Baptist minister as well as a dedicated abolitionist.

They presided over the continued construction and affairs of the school from 1871 to 1879, when they returned home to Brooklyn. An article from the Times-Picayune reveals the extent of the ties between the Chamberlain family as well as their continued generosity.

Mrs. Chamberlain had died the previous year. At the end of her life, she ordered that upon the settlement of her estate Leland would receive a $50,000 donation for the continued improvement and sustenance of the university.

Interestingly, this article also gives us a timeline as to when the school adopted the labor component of the curriculum.

Considering the news release, it is evident that Dr. Travers implemented the requirement for students to participate in campus maintenance as early as 1882. Jari Honora discusses these practices in detail in her article on Leland’s history, “Each student was required to spend at least one hour of the day in the industrial classes, doing work about the campus, or helping on the university’s farm which helped to defray costs for students who could not afford the full tuition. The total expenses for a boarding student averaged about eighty dollars a year.”(1) While some may argue that these practices were unfair to the enrolled students, it seems that the decisions to require a “labor component” actually reflect the university’s dedication to providing an affordable and quality education to freed slaves, as it allowed them to better maintain the grounds and defray boarding expenses.

The racial tension surrounding the history of the university should not come as a surprise to researchers, especially considering Leland was located directly next to Tulane the entirety of their duration in New Orleans.

In 1895, the Times-Picayune published the previously pictured article about Tulane Alumni vandalizing the campus of Leland University. “A Clash of Colors” could be interpreted as a play on words, as it demonstrates the racial tension between the two schools, but also comments on the act of vandalism that occurred. In short, Tulane had decided to paint their posts the school colors at the time, green and white. Leland, being located next door to Tulane, followed suit and painted their posts two different shades of blue.

The conflict arose when an alumni class from Tulane argued the two blue colors were, in fact, the colors of their graduating class, and thus argued the use of these colors was offensive to them as well as unacceptable. Not getting the response they desired, at least 50 students from the alumni class coordinated a plan repaint the posts of Leland “coal black” in the middle of the night. In addition to this unreasonable and hateful act, they carved skulls and crossbones into the posts marking the entrance to the school.

In 1900, Leland University celebrated 30 years of providing quality education to freed African American. Shortly afterwards, they elected a new president in 1901 by the name of Rev. Dr. R. W. Perkins.

From 1901 to the Great Storm of 1915, Leland stayed out of the papers for the most part, aside from their yearly graduation announcements. What essentially marks the end of Leland’s presence in the city of New Orleans is the Great Storm of 1915 since the school suffered damages amounting to around $3500, according to Dr. Perkins in a news article. However, Dr. Perkins also stated the school would reopen its doors and that officials would still be available on campus to assist students in registering for courses.

Not even two days later, the following headline hit the Times-Picayune.

Two things about this article are striking, the first being the word choice used to describe the university. The use of the phrase “negro college” seems indicative of feelings of white superiority during the time period as well as animosity towards the university. Why not just call the university by its given name?

The second striking point about this news release is that the trustees of Leland had actually been considering selling the school as early as 1912 because the once under-developed and less wealthy uptown area had become very wealthy with the construction of expensive homes and the surrounding Tulane & Loyola University. Because the land the school was built on was initially purchased for $20,000, the trustees knew the land was worth at least 5 times that amount by 1912. It is not surprising then, that the trustees jumped on the opportunity to make a massive profit on the sale of the land once the school was severely damaged in 1915.

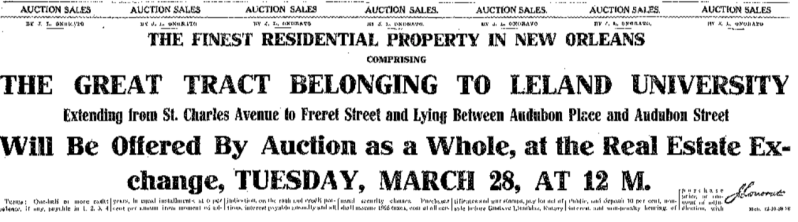

In 1916, the property was set to be auctioned on March 28, and was eventually purchased by a Mr. Robert Werk for $175,000. Mr. Werk later commented he had plans to turn the property into an attractive, urban residential environment with high-class homes.

Arguably, Leland is an example of the gentrification of Uptown New Orleans. The animosity towards the school’s presence in the city becomes even more apparent in an article published in the Times-Picayune where the author comments that Leland University was “wedging off the spread of the high-class residential section, and the fact that it was a negro institution was another handicap not only on growth but also on the prospects of the college settlement which had begun its evolution.” (2)

In March of 1922, the trustees of Leland University purchased land for $30,000 in Baker, Louisiana, which is not far north of Baton Rouge. It was argued that this location would allow the institution to further incorporate agricultural and industrial education into the curriculum.

While the desire to make a profit is not surprising, it is strange that the trustees would later argue it was better for the students to be in an area like Baker, as there were more agricultural opportunities and “they would feel more at home.” Considering Leland drew most of its student population from the city and the fact that Baker is a long distance to travel away from home, the claim that Baker was a better location for the students seems quite absurd.

After nearly ten years, the school in Baker finally opened in 1923 and normal classes resumed.

From 1923 to the time the school closed in 1960, there was little reporting of the school in the newspaper. The most notable events include talk of merging Leland University and Straight University, another college for African Americans, around 1929, and also the discussion of relocating the school back to New Orleans in 1930. Obviously the school never managed to relocate to its city of origin, but did continue to produce distinguished graduates in Baker until they permanently closed their doors in 1960.

Footnotes:

(1) Honora, Jari C. “Leland University in New Orleans 1870-1915.” Creolegen. N.p., 20 Sept. 2014. Web. 12 Nov. 2015. <http://www.creolegen.org/2014/09/20/leland-university-in-new-orleans-1870-1915/>.

(2) “Leland University,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 09/25/1927, p.34.

References:

- “Advertisement,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 03/12/1916, p.25.

- Campanella, Richard. “A Tale of Two Universities: Leland, Tulane and an Early Example of Gentrification.” Nola.com. Times-Picayune, 8 May 2015. Web. 12 Nov. 2015. <http://www.nola.com/homegarden/index.ssf/2015/05/before_tulane_before_loyola_th.html>.

- “A Clash of Colors,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 02/03/1895, p.9.

- “Congressional,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 02/18/1873, p.1.

- “Dr. Perkins Studies Negro Education,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 05/10/1901, p.3.

- Honora, Jari C. “Leland University in New Orleans 1870-1915.” Creolegen. N.p., 20 Sept. 2014. Web. 12 Nov. 2015. <http://www.creolegen.org/2014/09/20/leland-university-in-new-orleans-1870-1915/>.

- Leland University, New Orleans. Catalogue. v. 30-38 (1899/1900-1907/08). Atlanta, Ga.

- “Leland University,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 10/08/1915, p.4.

- “Leland University,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 03/17/1923, p.8.

- “Leland University,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 09/25/1927, p.34.

- “Leland University: A Well-Equipped Institution for the Education of Colored Peoples,” Times Picayune (New Orleans), 11/18/1886, p.8.

- “Leland University Celebrates its 30th Anniversary & Holds Graduation,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 05/09/1900, p.7.

- “Leland University Gets Building Site,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 03/14/1922, p.7.

- “Leland University to Join in Merger,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 04/24/1929, p.16.

- “Leland University the Recipient of a Donation of $50,000,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 12/30/1882, p.2.

- “Return of Leland University Sought,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 02/12/1930, p.2.

- Robinson’s Atlas, District 6, Plate 27, Location of Leland University in Uptown New Orleans. http://www.orleanscivilclerk.com/robinson/guide.htm

- “Trustees Order Negro College Property Sold,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 10/10/1915, p.60.

- “Valuable St. Charles Sites Go on Market,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 07/02/1916, p.38.

- “1923 Leland University,” Southern University & A&M College, Archives Department. 1923. <http://contentdm.auctr.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/suam/id/1511>