The rich broth that flows down your tongue. Those flavors cover every single taste bud as you slurp it down. The smooth rice noodles join in your flavorful journey, along with a variety of meats and garnishes. The hint of lemon and hoisin sauce, and perhaps sriracha, mixed in this one dish. Phở, or simply pho, has been made a mainstream staple of Vietnamese culture. It is the one of the many dishes people think of when hearing about Vietnamese food. It has been mixed and altered in many ways as it melded with the flavors of Vietnam and the world.

As a first generation Vietnamese American, pho has been my gateway to reconnecting with my culture. Its flavors are tied to my family, especially my bà ngoại, who makes the dish at home. I live for the days where her big pot of broth sits on the stove, and I can smell the beef bones and seasonings mingle with the air. When a special occasion is underway, such as a family member coming home, my bà ngoại, or grandma, always prepares a pot of pho. In a sense, it was a way to celebrate. For a while, however, it was just a delicious dish to me with no connection to it. I ate pho, simple as that; I was used to it as a regular home cooked meal. However, pho, as I didn’t come to realize, has a deep cultural connection to it. The soup has been through twists and turns to be where it is today. Pho is a testament to and representation of the adaptability of Vietnam and its people and more personally, the adaptability of my family as immigrants.

Pho’s origins are unclear to say the least. There exist many explanations for its existence and its rising. Nevertheless, the dish almost for certain originates in the north of Vietnam1 and has some connection to French colonialism2. Between the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century, French colonialism was at its peak. Due to French influence and demand, beef became much more readily available in Vietnam. As a result, a surplus of beef bones was produced2. With this now more available ingredient, vendors would come to experiment with it, richening their broths and creating pho bo, or beef pho. The dish gained more traction, starting in Hanoi and spreading outwards across Vietnam. Pho had gained popularity as it crossed between cultures and people, and it became what is now the acclaimed soup dish of Vietnam.

However, pho has waded through the waters of war the same as the Vietnamese. The Vietnam War led to millions of Vietnamese people being scattered from their hometowns with most people moving south of Vietnam or even immigrating to different countries in refuge. Pho and its various recipes came along with those people, and it has since travelled to broader countries, most prominently in America.

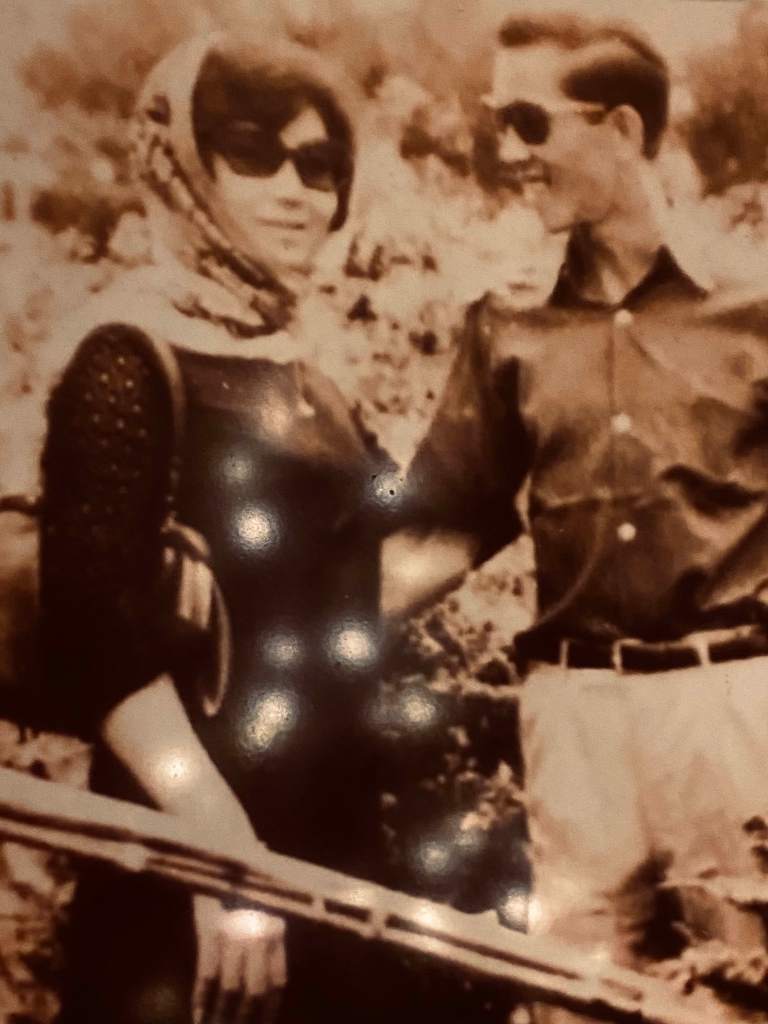

My bà ngoại was born in the southern province of Saigon, Vietnam in 1942. She was about in her teens when she had her first taste of pho. She had gotten it from one of the vendors in Saigon. She rolled the flavors on her tongue as she ate the food, and that was when she was determined to learn the recipe. She would watch vendors cook the soup and try to recreate the dish the same way. When she would find a better tasting pho, she would adapt and enhance her recipe. She was a great cook even in her youth, reminiscent of her mother. She had a tongue for flavor and could tell the recipe from a taste. But, if she did not, she was determined to find it out. My bà ngoại was like any other Vietnamese girl living in Vietnam. She would sell food with her family in Saigon and cook with her mom from her teens and adulthood. Her mom was the traditional household wife, cooking and taking care of the family at home. She would learn from her how to cook. Most prominently, though, she grew up poor. It was tough to get ingredients as a poor family in Vietnam. She couldn’t afford all the ingredients she needed to cook or even the best variety of meats available. She had to settle what she had. That was the reality of her life.

Years after the Vietnam War ended, she immigrated to the Philippines for a year in 1985. It was the first stop refugees were allowed to go to. There, she sold xôi, a dish consisting of sticky rice and other ingredients, and other rich dishes on the streets to raise money for the family, which she still makes today. It was a tough time, to say the least, to migrate to and from places in these conditions. Making these foods was a means to an end. That was the harsh reality of my grandma’s circumstances.

She immigrated to America the next year in 1986, where she faced numerous challenges. Among the perhaps harsh life of immigrating to a new place all over again, some ingredients typically common in Vietnam were not found anywhere in America. An example of this being nước mắm, or fish sauce. Many dishes in Vietnam use fish sauce for a variety of purposes. For it to be such a common ingredient, it was hard not having it available. She had to make the fish sauce by scratch, which was not easy when starting out in America. To make things worse, she had to make her foods more bland and not as flavorful as she would have cooked in Vietnam. These were some of the challenges she faced as a Vietnamese immigrant in America.

However, with time, she and the family were able to rise in money and class. Now being a middle-class family, she has been able to purchase better ingredients, spices, etc. to make her dishes. Her pho became much more manageable to make, and she had the luxury of trying out new recipes and ingredients in her pho, along with her many other dishes. She says now that it’s better in the United States to make food. That does not mean that those dishes are better tasting than if she made it in Vietnam, but she was able to attune herself to American middle-class life.

As years went by, I would come to be as a first generation Vietnamese American. I was put into an American school with American teachers. I was taken to American places and ate American foods. I was living the American life. My Vietnamese identity was a subset of my American identity it seemed. I was not raised to speak Vietnamese and did not partake much into Vietnamese culture as I should have. This was not the fault of my parents, rather it was just the circumstances that blocked me from really deepening myself in Vietnamese culture. As I grew up, I did end up having a lot of Vietnamese friends. However, it was the same for them as it was for me. They were Vietnamese Americans who leaned more into the American lifestyle. I was living the American life, yet I was constantly reminded of the divide between me and my own culture.

Since I did not know Vietnamese, I was left out of solely Vietnamese groups. I was a tier below those who were deeper into their culture than I was. I was jealous. I was jealous that they were “more Vietnamese” than I was. I felt ostracized in my own culture. That fact did not help with me being a minority in America as well. I was ostracized because of my race and ethnicity. I received racist comments from those around me because of my minority status. I did not feel like I had any sense of community in any place of who I am. I felt like an anomaly in an anomaly.

To my family, though, I was me. I still partook in the Vietnamese traditions my family took me to. I enjoyed activities like bầu cua, a Vietnamese gambling game, and receiving li xi’s (red paper slips with money given to wish those for good luck) during Lunar New Year. I’ve enjoyed many different types of Vietnamese food. With that, I ate many bowls of pho. Pho was one of my favorite dishes. It was always something to look forward to. But more importantly, it made me feel closer to my culture. I was partaking in years of tradition through this simple bowl of pho. I was digesting, metaphorically, a piece of Vietnam. Pho was a dish that reminded me that I was still Vietnamese. It reminded me that this was my culture. The warm broth was the ignition to reconnect myself to Vietnam. Pho was, metaphorically, my culture, wrapped in one diverse and flavorful dish.

Pho has stood the test of time as a representation of the Vietnamese immigration story, at least to my personal and familial story. Pho is a dish that represents years of struggle, but also years of culture. Pho and the many dishes of Vietnam are what reconnects me to my identity, and as I continue to reconnect with that identity, I will continue to slurp down a bowl of pho along the way. So, I grab my chopsticks to settle on another bowl. I slurp up the noodles, connecting the past to myself. And once I’m done with it, I can feel proud, knowing that I am partaking in a vibrant culture. One that I can call my own.

Notes

- Greeley, A. (2002). Phở: The Vietnamese Addiction. Gastronomica, 2(1), 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2002.2.1.80

- “The Story of Vietnamese Pho.” Vietnam Tourism, 2019, vietnam.travel/things-to-do/history-pho.