“Laissez le bon temps rouler-” the phrase etched into the mind of tourists worldwide when thinking of New Orleans. New Orleans is the city of the good time, often visited specifically for this reason. With the university nightlife of uptown, the bustling Bourbon street downtown, and the unique Mardi Gras parades spanning St. Charles, there truly is no other city like it. The let loose attitude of the city has been echoed by generations of tourists, stemming back hundreds of years to the very beginnings of its implementation into a young America. This long standing tradition as an alcoholic’s paradise seems to brush over a decade of federal law incompatible with this view- the instating of the 18th amendment and the beginning of the prohibition in 1920.

Tourists and temporary residents of the early 19th century paint pictures of a city of lively social events, a blend of the most fun parts of the various world cultures inhabiting New Orleans. A letter sent on September 17th, 1807 by Nathaniel Cox, a temporary resident of New Orleans from Virginia, details his experiences in both coffeehouses and ballrooms. Coffeehouses of the 19th century varied wildly to those of today, with alcohol being commonly sold to patrons, as shown in the liquor licenses of the time. Cox uses these locations as framing for discussion in favor of sharing spaces with other cultures, but his mentioning of coffeehouses in particular as a spot for social mixing is indicative of alcohol’s service impacting social life in New Orleans. He sees his observance of the blended culture and nightlife of New Orleans as “you would see the actors perform”

Later into the century, L.H. Webb, a North Carolinan Methodist who spent around a year in New Orleans selling books, wrote in his journal about the traveling circus that made a stop in the city. He ultimately admits the circus in New Orleans is beautiful, but prefaces his thoughts with the idea that the circus displays, “vulgarities, sights, and sounds offensive to strict morality.” This “strict morality” when compared later to the rhetoric used by temperance advocates, especially southern methodists, most certainly included the consumption of alcohol by the audience.

Serving liquor in the 19th century was not cheap, with a liquor license from 1856 requiring a sum of 500 dollars be paid by the bar to the treasury as a licensure fee. The fee was a risk willing to be taken by bar owners of the 19th century, with confidence in their minds that the amount of profit from the bars would be worth it, suggesting just how popular these bars were. The notion of a party city and the freedom of limitless alcohol consumption was already present in the 19th century, and was on track to remain that way throughout the 20th.

With the 20th century, came the rise of ideas troubling the coffeehouse, bar, and cabaret owners of the previous century- the temperance movement. The 1910s were a decade of fierce debate over the topic of prohibition and the injection of “morality,” and by 1918, the 18th amendment was seeking ratification. The battle over ratification in Louisiana was close, with northern parishes being dry and housing the state’s Anti-Saloon League, and southern parishes fighting back against its ratification1. The amendment and subsequently the wartime prohibition act marginally passed, meaning certain doom for the alcohol-fueled spirit of New Orleans, right?

At the same time the legislature debated these acts and amendments, the red-light district of New Orleans thrived. A blue book from the late teens describing local prostitutes and brothels had the preface that, “it is the only district of its kind in the States set aside for the fast women by law, 2” highlighting the position that New Orleans was in at the time. The book contains 100 pages of names and addresses to the brothels of their residence, sorted by race and age. It reads like a yellowpages of prostitution, but with a very distinct set of ads alongside the names. Half of the pages in the blue book were advertisements for alcohol. Some were for the bars themselves, coffeehouses, and cigar shops, but a good portion of them were for wholesale alcohol, directed at bar owners. This book coinciding with the introduction of the amendment sets the stage for the future of alcohol in New Orleans over the next decade, a culture of alcohol that is already so heavily entangled with legal gray area and “seedier”aspects of the city, will continue to thrive no matter the conditions created by the law.

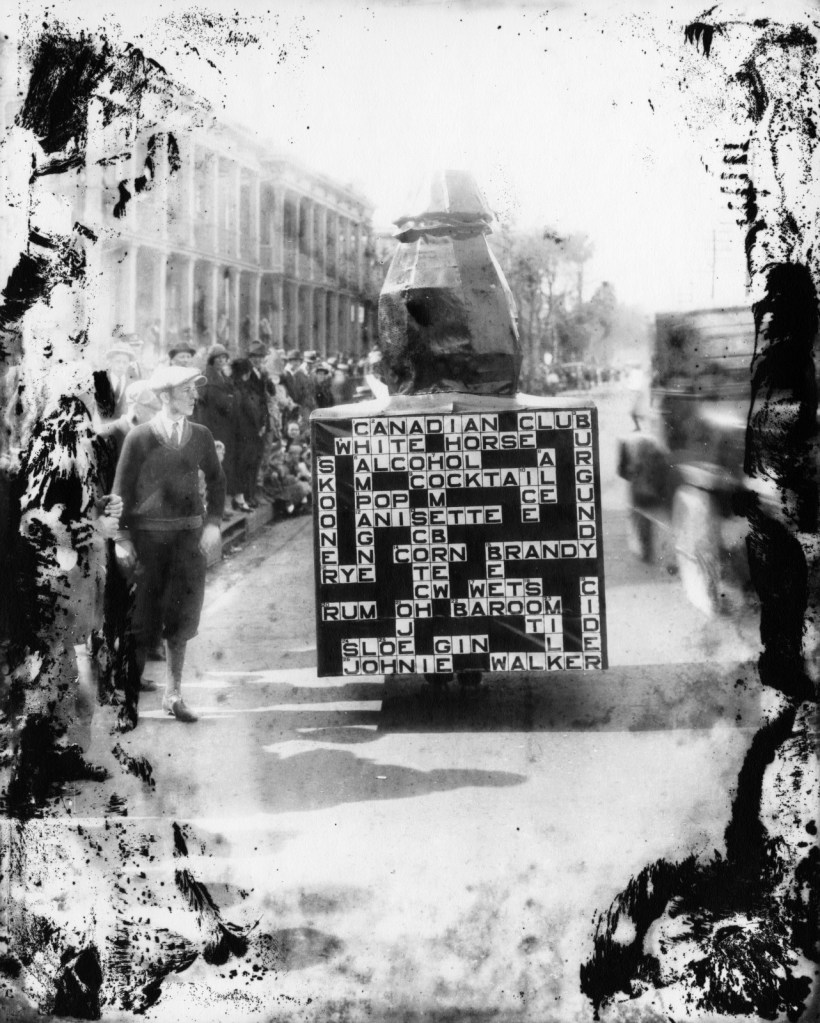

In January 1920, prohibition became the law of the land. Not so shockingly, the day came and went, with New Orleans liquor culture remaining mostly in-tact. Although quickly moved underground, alcohol remained pumping through the city’s veins. In the early days of prohibition, establishments selling alcohol invented codes to order drinks. A lunch room at Union and Carondelet had a code relating to the number of fingers shown to order strengths of liquor, and after the lunch rush would convert into a speakeasy3. Raids rarely faced these somewhat open sales of liquor. By the mid-20s, the attitude surrounding alcohol in New Orleans during prohibition went from not caring to really not caring about federal law. The now defunct coding system was so out in the public eye that jokes and satires regarding the enforcement of prohibition could be found during Mardi Gras. In 1925, the code system and federally published terms referring to alcohol appeared on a comical Mardi Gras float. The decanter shaped float features a crossword attached to the side, with intersecting terms of the time. The people photographed around the float are laughing, smiling, and yelling, contributing to the light-hearted feeling of the topic and the seriousness lacking from the discussion around prohibition in New Orleans.

The sentiment around the laws in New Orleans did not negate how difficult it was for sellers of the time to obtain liquor. For the past 6 years by this point, the underground bootlegging network had begun to firmly plant itself within the bar scene of New Orleans. As seen in the 1910s with the association between wholesale liquor and the red-light district, the purchase of alcohol had long been connected to crime. Bootlegging began in the early days of the prohibition, with the peak of its organization and violence coming at around 1925, the same time morale around alcohol had reached a point of making the satirical float.

Whiskey was among the most smuggled alcoholic beverages4, and just so happened to be available via prescription. The suggested max amount prescribed by physicians was 6 quarts a year, to be sure the liquor wasn’t consumed for anything other than medicinal value. Two prescriptions from the city dating to 1930 counteract this “suggestion.” One pint of whiskey, to be taken 3 times a day, until it’s cancellation in 1931, had been prescribed to Salvatore Cammella. 3 pints of whiskey a day for a year equals about 547 quarts of whiskey for the duration of the prescription. The records on this particular patient have been lost to time, but with that amount of liquor, and the known activity of bootlegging around the area, it is not hard to imagine the use of this “medicine.” Although the wholesale of alcohol had been pushed to such means as crime rings, prohibition investigator Izzy Einstein claimed New Orleans was the quickest place to find a drink5.

The efforts of Temperance advocates within the city to crush the culture of alcohol also continued throughout prohibition, with pamphlets being sent city-wide to deter New Orleanians from the “sinfulness” of alcoholism. One titled “Let Your Conscience be Your Guide” published in 1931 by D. L. Watson via the Temperance Foundation Incorporated6 has 21 pages disavowing the use of alcohol. The pamphlet takes a multi-faceted approach, starting with a page full of bible verses against intoxication. It then goes into disease, infant disease, and costs. Injected into the “science” of sobriety is more bible verses, deeply entrenching the temperance movement with religion, a fact Watson says he debunks on the first page. The pamphlet reads frantic and fanatical, as though the organization knew it would fall on deaf ears. On deaf ears it most certainly fell.

Published the same year as the pamphlet, a map and timeline of cocktails was created by Collins C. Diboll. The poster has drawings of various bars and opera houses, with a wheel of cocktails in the center. The wheel contains not only the name of the drinks, but all of its ingredients, including the liquor. This poster was an open promotion of liquor, and is formatted like a cocktail menu featuring locations where patrons could buy the drinks. The poster is lined with quotes about drinking, like an “The End is Near” billboard for the 18th amendment. Heading into the 1930s, 77% of Louisianians were in support of changing prohibition. 2 years after the publication of both the pamphlet and the poster, prohibition was officially over, and what was sure to be a joyous and drunk day for the rest of the nation was an averagely intoxicated day for the people of New Orleans.

- Jackson, Joy. “Prohibition in New Orleans: The Unlikeliest Crusade.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 19, no. 3 (1978): 261–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4231785 ↩︎

- Blue Book. Permanent Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection. https://catalog.hnoc.org/web/arena/search#/entity/thnoc-archive/2012.0141.1/blue-book. ↩︎

- Jackson. “Prohibition in New Orleans.” 267 ↩︎

- Jackson. “Prohibition in New Orleans.” 267,72 ↩︎

- Jackson. “Prohibition in New Orleans.” 269 ↩︎

- Watson, D.L. “Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide,” 1931. Permanent Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection

↩︎

Works Cited

Blue Book. Permanent Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection. https://catalog.hnoc.org/web/arena/search#/entity/thnoc-archive/2012.0141.1/blue-book.

Diary Entry, 1853. L.H. Webb Diaries, Louisiana State Museum Historical Center

Diboll, Collins C. “The How, When and Where of Discriminating and Enjoyable Drinking,” 1931. Collins C. Diboll Private Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection. https://catalog.hnoc.org/web/arena/search#/entity/thnoc-archive/2007.0084.2/the-how%2C-when-and-where-of-discriminating-and-enjoyable-drinking

Jackson, Joy. “Prohibition in New Orleans: The Unlikeliest Crusade.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 19, no. 3 (1978): 261–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4231785

Letter to “Daniel,” September 17, 1807. Letters of Nataniel Cox to Gabriel Lewis, Louisiana State Museum Historical Center. Photo by Author.

License for Selling Spirituous Liquors, 1856. C.D. Wells Collection, Louisiana State Museum Historical Center. Photo by Author.

Liquor Prescriptions, 1930-31. C.D. Wells Collection, Louisiana State Museum Historical Center. Photo by Author.

Mardi Gras Costume, 1925. Charles L. Franck Studio Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection. https://catalog.hnoc.org/web/arena/search#/entity/thnoc-archive/1979.325.3908/mardi-gras.-circa-1925%2C-costume%2C-prohibition

Watson, D.L. “Let Your Conscience Be Your Guide,” 1931. Permanent Collection, The Historic New Orleans Collection