“Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you who you are” – Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin

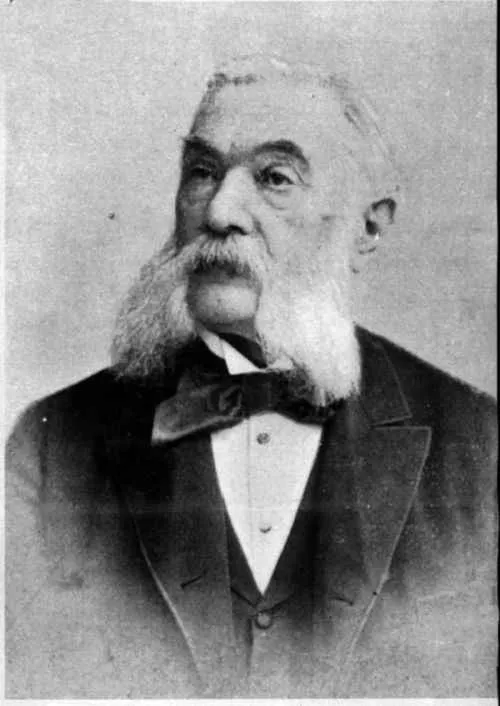

There is nothing quite so comforting and delicious as a good serving of spaghetti and meatballs. Believe it not, though, spaghetti and meatballs did not initially come from Italy – and instead it was an invention of Italians who immigrated to the United States.[1] During the time that these Italians were emigrating from their homeland, Italy had only recently been unified into a singular state. Prior to this, what we understand as Italy today was actually a large cluster of independent city-states, including notable locations such as Milan, Florence, Sicily, etc. It is no wonder, then, that Italian food at this time wouldn’t have been a monolith. Because each of these city-states had their own culture, it stands to reason that their food would have its own culture, too. There is one particular person that can be thanked for the compilation of all of these local recipes: Pellegrino Artusi. His cookbook documented a host of recipes from all around the Italian peninsula, compiling them into the first Italian cookbook – giving anyone who has access to the recipes an idea of what traditional Italian cooking really looks like. As time passed and Italians made their way to America, their recipes evolved and changed with their new environment. More access to ingredients during the late 19th and early 20th century allowed for this evolution of both culture and recipes.

Before getting into the meat (pun intended) of this debate, the question of who Pellegrino Artusi is and what was going on during the time of his recipe compilation must be answered. Artusi was born in Forlimpopoli in 1820, and spent his life there up until the age of 32 when he moved to Florence, where he would live out the rest of his life. It was there in Florence in the year 1891 that Artusi would compile La Scienza in Cucina e l’ Arte di Mangiar Bene (translated into English as The Science in the Kitchen and the Art of Eating Well), the first Italian cookbook.[2] Within these pages, there are 790 Italian recipes which Artusi collected, all designed for home cooking and based off of Italian recipes from all around the peninsula. 1891 was exactly twenty years after Italy unified, meaning that before this there was no real compilation of Italian cuisine across the entire nation – making Artusi’s cookbook incredibly significant. It serves as a record of all those traditional Italian recipes that existed pre-unification in the various Italian city-states, and presents them all together as one unified Italian cuisine.[3] These recipes, or at least some of them in one form or another, would have been familiar to the Italian immigrants coming to America from their home country.

For an example of Artusi’s recipes, let’s look at his rendition of meatballs – traditionally called polpettes. Artusi is recorded to have said that polpettes are “a dish that everybody can make, starting with the donkey,”[4] but he still provides a small tutorial within his cookbook nonetheless. After all, how could a donkey ever begin to make meatballs without ingredients? Artusi’s recipe calls for boiled meat, parmesan cheese, spices, parsley, garlic, eggs – pretty standard stuff for a meatball recipe. However, included amongst these ingredients are a strange addition: pine nuts and raisins. They’re to be formed into balls “about the size of an egg”, fried in oil or lard, and served with an egg garnish.[5] A simple recipe, and yet so different from the classic savory meatballs that Americans would be accustomed to. Raisins and pine nuts hint at a sweeter flavor, and the frying technique hints at a different texture as well – especially considering the meat is pre-boiled. Altogether, an Artusian polpette is nothing like the Italian-American meatballs known and loved today.

So why did the recipe change? When waves of Italian Immigrants were coming to America, their lifestyles adapted to their new environment. These immigrant families were still poor by American standards, but they still earned a lot more money than they did back in Italy. They could readily afford to buy meat in such quantities that it became a staple in their diet, rather than a luxury.[6] In the United States, it didn’t matter much where in Italy these immigrants came from – they were all Italians, brought into close proximity with one another and able to exchange recipes and techniques readily. Notably, though these immigrants were from a wide variety of places, the vast majority came from Southern Italy – like Sicily and Calabria – so modern Italian-American cuisine definitely has more of a southern Italian flair to it.[7] But, because it was easier to acquire food, eating was no longer about just surviving, it was about eating well, just as Artusi would say!

These changes culturally affected the new Italian-Americans. For one, Italian-American women’s role began to morph. Italian moms and grandmothers (nonna in Italian) in their home country struggled to feed their family, but now they were proud home chefs. Feeding their (grand)children was and still is a way to express love, and just as well a way to preserve their culture in a small way. Patrizia La Trecchia, and Italian-American scholar, remarked that despite struggling to understand her Nonna Lavinia’s southern Italian dialect (Patrizia spoke a more standard Tuscan dialect), they connected through the food that she made her. The language they spoke may have been different, but the food was a language all its own and allowed the two to connect even still.[8] Thinking about it while understanding the historical context, it makes sense. A mother that once could barely afford to feed her children now was blessed with the opportunity to feed them well every single day – so of course not only is she going to give them food, but good food. It wasn’t just about the food itself, though, but the process of making it together. Italian-American culture also developed a culture of cooking together as connection, as it was yet another way of sharing their culture and bonding with the younger generation. Christine DeLucia documents an oral history interview with her aunt who states that “Cooking was an all-day affair, and it was really a lot of fun.” Her touching account of cooking with her grandmother indicates the importance of culture-sharing through food amongst Italian-Americans.[9] Though their recipes have changed over the past hundred or so years, the culture of expressing love through cooking and eating never has.

To cap this off, let’s look a traditional Italian-American recipe for “Sunday Sauce”, or spaghetti and meatballs. Now, initially, I was going to use a recipe from celebrity chef Giada Di Laurentis. She’s a good chef, and I’ve enjoyed many of her dishes in the past – my dad has a huge cookbook full of them. However, as I was researching and writing for this project, I had a realization. All this time, I’ve being trying to emphasize the importance of home cooking and family within Italian-American food. I feel as though using a celebrity chef like Giada, however talented she may be, defeats the purpose of that. So, I found a recipe on YouTube, specifically searching for family recipes – and I found the perfect one. So, without further a due, let’s get cooking.

This recipe comes from Antionette, a third generation Italian-American whose family originates from Naples. She watched her father make the meatballs and sauce every Sunday, and now she’s sharing her recipe with the viewers. It’s a very traditional recipe one would expect: all the typical ingredients (tomato sauce, finely chopped onions, fresh garlic, basil, olive oil, etc.) are there. For the sauce, saute some Italian sausage in a pot with extra virgin olive oil, garlic, onions, and tomato paste – then combine these ingredients alongside crushed tomatoes, red wine, basil, and tomato sauce in a pot and allow to simmer for an hour. It’s a standard recipe for tomato sauce, and the meatball recipe is no different. Ground beef, breadcrumbs, some spices – the recipe itself is not necessarily the point.[10] I’ve already expressed the evolution of these ingredients from Artusi’s original polpette recipe: there is more meat because Italian-Americans could afford more, and some ingredients were simply not as available in the United States as they would have been in Italy, so changes had to be made. What matters most is the tradition behind the recipe itself. The recipe has been passed down from generations, and now in the modern era, YouTube viewers can participate in a little piece of Italian-American culture from their own kitchens at home.

[1] Esposito, Shaylyn. “Is Spaghetti and Meatballs Italian?” Smithsonian.com, June 6, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/is-spaghetti-and-meatballs-italian-94819690/.

[2] Editorial staff . August 30, 2019. “Pellegrino Artusi, the Inventor of Italian Cuisine.” La Cucina Italiana, August 30, 2019. https://www.lacucinaitaliana.com/trends/restaurants-and-chefs/pellegrino-artusi-inventor-of-italian-cuisine.

[3] Montanari, Massimo, and Beth Archer Brombert. “The ARTUSIAN SYNTHESIS.” In Italian Identity in the Kitchen, or Food and the Nation, 47–52. Columbia University Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/mont16084.12.

[4] Esposito, Shaylyn. “Is Spaghetti and Meatballs Italian?” Smithsonian.com, June 6, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/is-spaghetti-and-meatballs-italian-94819690/.

[5] MacAllen, Ian. “Artusi’s Polpette.” Red Sauce America, June 17, 2022. https://www.redsauceamerica.com/blog/artusis-polpette/.

[6] It’s worth noting that the meat they were eating wasn’t prime rib or anything fancy, it’d be more equivocal to ground chuck.

[7] Esposito, Shaylyn. “Is Spaghetti and Meatballs Italian?” Smithsonian.com, June 6, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/is-spaghetti-and-meatballs-italian-94819690/.

[8] La Trecchia, Patrizia. “Identity in the Kitchen: Creation of Taste and Culinary Memories of an Italian-American Identity.” Italian Americana 30, no. 1 (2012): 44–56. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41440432.

[9] DeLucia, Christine. “Negotiating the Hyphen: An Evolving Definition of Italian-American Identity.” Italian Americana 22, no. 2 (2004): 201–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29776963.

[10] “Antoinette’s Kitchen: Episode 1 | Sunday Sauce with Meatballs & Sausage” posted March 13, 2023, by Antionette’s Italian Kitchen, YouTube, 12 min., 34 sec., https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fkLteaF2DLY.