The Origin of Mantou Steamed Buns

The origin of bao buns dates back to the third century during the Three Kingdoms period in China. After securing a victory in a battle, a well-respected Chinese military strategist, Zhung Liang, found himself in a bit of a pickle. While Liang and his soldiers were returning home, they reached an unsurpassable river protected by a Diety, where they learned of the gruesome folk tale connected to this river. Apparently, no soldier could successfully pass through this river unless they fulfill the Diety’s request. In Liang’s case, he must sacrifice fifty soldier heads and throw them into the river “as a peace offering” to the Diety (Buy and Bite Chi-Li). Unwilling to sacrifice any of his soldiers’ heads, Liang concocted a devious plan to throw fifty dome-shaped steamed bao buns into the river. To their surprise, the river Diety believed the steamed buns were actual soldier heads, so the Diety created a path for them to cross the river safely. This event sparked the the term, Mantou (馒头) in reference to Chinese steamed buns, which translates to “barbarian heads” in Chinese.

Following this event, mantou (馒头) became a popular food item to prepare because of its simplistic and unique taste. These traditional Chinese steamed buns were initially served without any type of filling inside. However, as technological advances and cultural influences emerged, different regions in China (as well as neighboring Asian countries like Thailand, Vietnam, etc.) developed their own version of the traditional montou steamed buns by incorporating different types of filling inside the buns. When any sort of filling is added to mantou, they are then referred to as boas.

Depending on the region in which people lived in China (northern or southern regions), boas were made using different key ingredients. For instance, the most common type of baos, prepared in the regions of northern China, was made using wheat flour since “wheat was cultivated in vast amounts in these regions. Thus, bao became a staple part of their diet” (Buy and Bite). In contrast, people who lived in the southern regions of China prepared baos using rice flour instead. It is clear how important agriculture and climate affects how different regions develop their own versions of the same dish.

As Chinese culture influenced surrounding areas, the popularity of bao buns spread further across the continent and eventually reached America. How could this authentic bao recipe make its way across the ocean and have an impact on American culture?

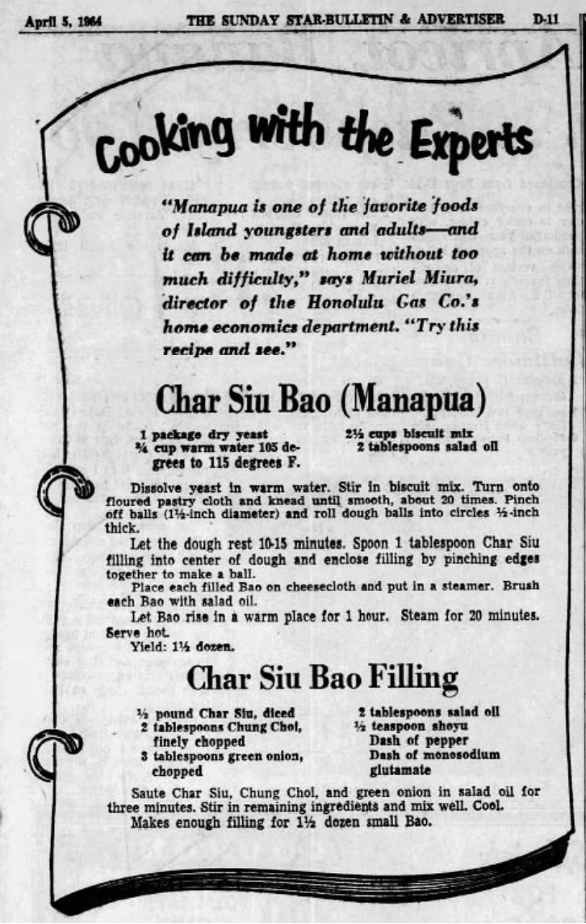

The earliest recorded newspaper clipping of a Hawaiian-infused bao recipe (“Cooking with the Experts”).

The Hawaiian newspaper, “The Honolulu Advertiser,” reported the earliest evidence of baos in 1961. In various Hawaiian newspapers throughout the 1960s published additional articles and recipes, such as this newspaper clipping highlighting Mrs. Lau’s authentic Hong Kong Bao recipe that she used back when she still lived in Hong Kong, China.

The image above shares a traditional Chinese bao recipe influenced by Hawaiian culture published in “The Honolulu Advertiser” in 1964. This Hawaiian version of a sweet yet savory bao bun with Cantonese influence incorporated. “Char Siu” is the Cantonese term that translates to steamed barbeque pork bun, and “manapua” is the Hawaiian term for these baos.

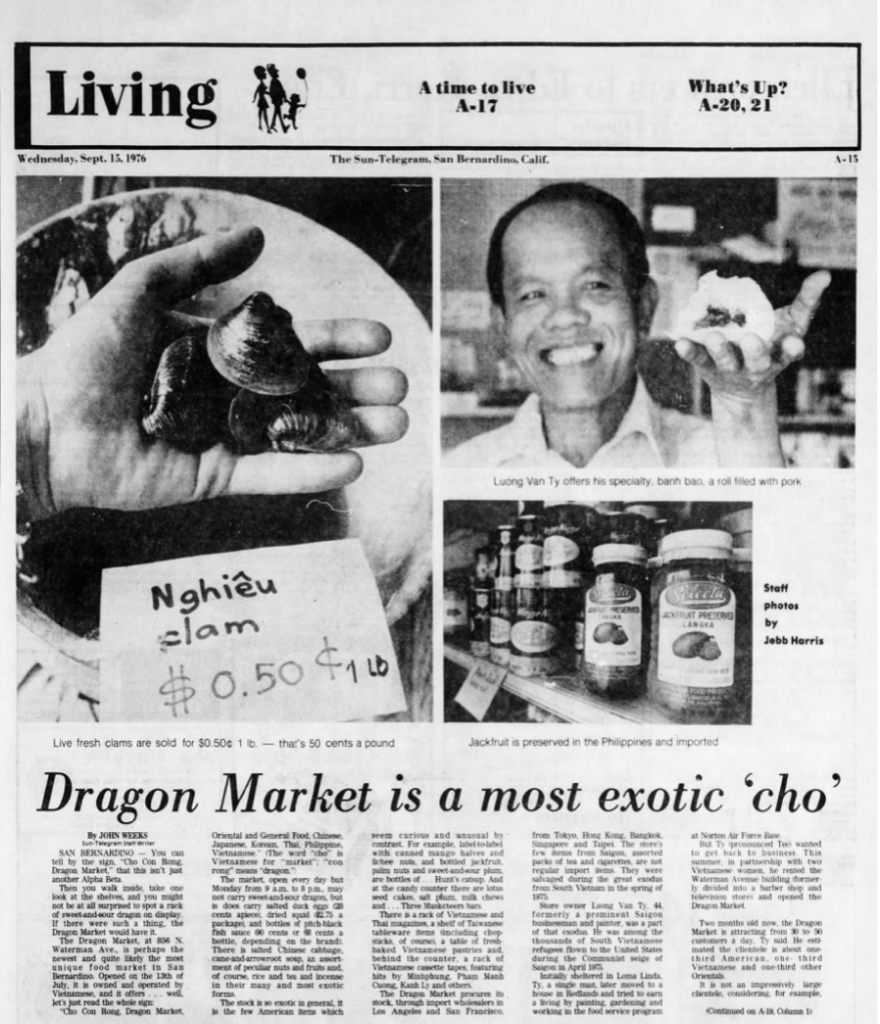

Towards the mid 1970s, the influence of baos made newspaper headlines in California and Michigan. The newspaper clipping above is from a 1976 California newspaper called “The San Bernardino County Sun.” As described in the article, this Vietnamese-owned market, Dragon Market, supports and sells Chinese, Japanese, Philippines, and Vietnamese cultural foods, such as Luong Van Ty’s homemade bánh baos (shown in the top right image above).

Given the timeline of these newspaper publications, we can infer that the gruesome conditions of the Vietnam War prompted the emergence of baos in other countries as immigrants escaped their native country in search of safety.

It all Starts With Grandma’s Cooking

Growing up with a grandmother who has a passion for cooking traditional Vietnamese dishes, I have been fortunate enough to learn her techniques and her “recipes.” Recipes is in quotation marks because an interesting fact about my grandma is that she estimates all the measurements when she cooks. Since she has been cooking various Vietnamese dishes for years, she knows the right amount of each ingredient to add by just looking at it or pure muscle memory. Some people may be skeptical about her estimations, but I believe this is the reason why her cooking is unique (and delicious)!

Of the various Vietnamese dishes she cooks, she is known for her bánh baos, which is the Vietnamese term for steamed bao buns. In Vietnamese, “bánh” refers to food that is similar to bread or cake. Baos are an important part of Asian culture just as bread may be important to French or American cultures.

Premixed "bọt bánh bao" flour Grandma Mai uses as the base of her dough (Asia Mart).

Whenever she makes a batch of bánh baos, she makes enough for all her children and grandchildren. One batch typically makes about forty bánh baos. This requires a decent amount of preparation before assembling the bánh baos. There are various types of fillings to include in bánh baos (savory or sweet), but Grandma Mai keeps it simple. She incorporates seasoned pork, lạp xưởng (Chinese sausage), and boiled eggs in her bánh baos. She uses a pre-packaged wheat flour mix as the base of her dough (northern Chinese influence). This “bọt bánh bao” mix can be found in almost all Asian markets and includes wheat flour, salt, and baking soda. In addition to this mixture, she adds:

1 chén of self-rising flour

2 chén(s) of granulated sugar

3 tablespoons of oil

1 ½ chén of whole milk

Keep in mind that rather than using the term “cup” as a measurement, she uses a “chén” to measure her ingredients. “Chén” translates to one “small bowl” in Vietnamese. First, add all the dry ingredients into a large mixing bowl, then add the wet ingredients. Hand mix the wet and dry ingredients to make sure the dough is well-incorporated. Use a folding technique to evenly mix the dough while also preserving the fluffiness of the dough. Once the dough has a thick, smooth consistency, completely cover the dough and allow it to rise for about 30-40 minutes (in complete darkness).

In the meantime, use this time to prepare the filling for the bánh baos. Grandma Mai boils 10-12 eggs for about 10 minutes for the perfect hard-boiled eggs. While the eggs are boiling, weigh out about three pounds of ground pork meat (fun fact: she has her own meat grinder machine imported from Vietnam!). Next, season the meat with:

- tablespoon of salt

- tablespoon of sugar

- tablespoon of grinded pepper (or desired amount)

- ½ chén of diced onions (partially cooked)

Thoroughly mix the ground pork meat with the seasoning listed above. Before adding them to the meat, make sure to boil the diced onions to cook down the pungent raw onion taste into a more subtle onion flavor. Once the meat is evenly incorporated, use your hands to mold the meat into decent-sized meatballs (about the size of a ping pong ball). Then, refrigerate the meatballs until you are finished with the filling preparations. This seasoned meat recipe makes about 40 meatballs.

Periodically check on the boiling eggs. Once they have been boiling for about ten minutes, dump out the boiling water and soak the hard-boiled eggs in cold water to stop the eggs from cooking any further. Leave the eggs to cool while preparing the lạp xưởng (Chinese sausage). These Chinese sausages are used add the perfect savory flavor to many Vietnamese dishes.

First, peel off the casing off the lạp xưởng and cut them into thin, diagonal slices. After, carefully deshell the hard-boiled eggs, run them through water, and use a thread method to cut each egg into quarters (horizontally) to ensure clean, precise cuts.

Kam Yen Jan brand Chinese sausage is recommended (Kam Yen Jan)!

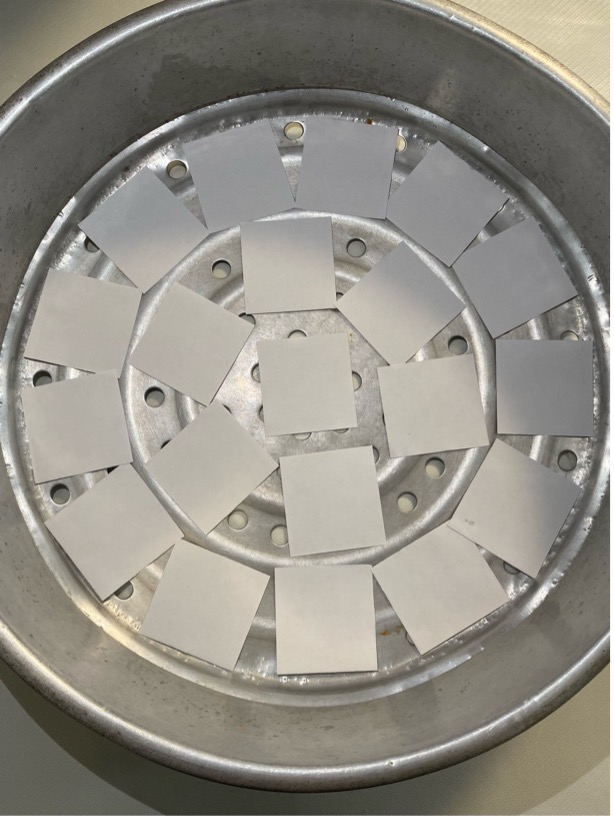

Now, we are ready to assemble the bánh baos! Prepare a large steamer pot with square-shaped paper lining to place each bánh bao on.

Check on the progress of the dough, and once it rises, sprinkle a generous amount of flour on a clean surface and plop the risen dough on top. Divide and cut the large blob of dough into smaller pieces (enough dough for one bánh bao). Use a pin roller to roll each small piece of risen dough into a circular shape (roll the dough evenly vertically and horizontally). Once you form a decent circular dough, place the seasoned meatball in the center of the dough, add the egg slice on top of the meatball, and line four slices of lạp xưởng along the sides of the meatball. Lift the dough edges upward to create a dome-shaped bao. Pinch and twist the excess dough off the top, and place the bao on a paper lining. Depending on the size of your steamer pot, separate the baos into batches. Steam each bánh bao batch for about 25 minutes (each batch includes about 20 baos). Lastly, leave the baos out to cool and enjoy your very own Grandma Mai bánh bao!

Bibliography

“A Brief History of Bao.” Chung Ying Cantonese, 16 Sept. 2019, http://www.chungying.co.uk/about/blog/a-brief-history-of-bao.

“Asia Mart.” https://asiamartsr.com/products/pyramide-bot-banh-bao-mixed-flour.

Buy and Bite Chi-Li. “History of the Bao Bun.” Buy & Bite, Buy & Bite, 11 Aug. 2021, http://www.buyandbite.co.uk/post/history-of-the-bao-bun.

“Dragon Market is a most exotic ‘cho’.” The San Bernardino County Sun, 15 September 1976, p. A. 15. Newspapers.com.

“Cooking with the Experts.” The Honolulu Advertiser, 15 October 1961, p. E.3. Newspapers.com.

“Cooking with the Experts.” The Honolulu Advertiser, 05 April 1964, p. D.11. Newspapers.com.

“Kam Yen Jan, 腊肠, Chinese Sausage (Lap Xuong Sausage), Asian Sausage, Thai Sausage, Chinese Sausage Lap Cheong, Taiwan Sausage.” Amazon, https://www.amazon.com/Kam-Yen-Jan-Chinese-Sausage/dp/B09SGXK3JG.